Trimethylsulfoxonium Bromide: A Deep Dive

Historical Development

Trimethylsulfoxonium bromide did not arrive out of nowhere. Its story tracks back to research in organic chemistry that sought out new ways to transform carbon skeletons. Early discoveries in the 1960s revealed the value of sulfoxonium salts as methylene donors. Chemists tinkering with oxides like trimethylsulfoxide and the reactivity of methyl bromide came to see trimethylsulfoxonium bromide as a key intermediate. Over the decades, teams at both universities and chemical plants learned to handle and purify this compound for more predictable lab results. Its reputation grew in synthetic labs because reactions could be scaled up or down, making it a favorite for seasoned chemists. From the moment it showed up in journal articles, curiosity about its broader utility never really went away.

Product Overview

Trimethylsulfoxonium bromide lands in the class of organic salts that frequently end up on a chemical shelf ready for use as a methylidene transfer agent. It takes shape as a crystalline solid, often white, sometimes showing a faint pink tint due to trace impurities. Pharmaceutical makers, fine chemical suppliers, and university stockrooms keep it supplied not just because it solves technical problems but because it survives storage and typical transport conditions with little drama. That stability opens doors for use in both teaching and scaled industry. Whenever a synthetic chemist wants a methylene ylide, they reach for this one as a simple starting point. You don’t find it in everyday consumer products, but its footprint becomes visible across semisynthetic drug manufacturing, advanced materials research, and in niche plastics innovation.

Physical & Chemical Properties

Put a sample of trimethylsulfoxonium bromide on a balance, and you get a molecular weight just over 215 g/mol. Salts like this usually melt around 200°C; this one starts decomposing before it reaches a clear liquid pool. Solubility favors polar solvents: toss it in water, DMSO, or methanol, and it vanishes into solution fairly quickly. Handle it gently and avoid getting it wet in storage—that prevents clumping or caking. Chemically, it presents a classic sulfoxonium group with three methyl arms and a bromide counterion. The molecular structure makes it stable under standard lab conditions, but it does not fare well in strong bases or acids. Mix it with sodium hydride or similar reagents, and you get reactive ylides in seconds.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Manufacturers ship this compound in tightly sealed HDPE bottles or glass jars, usually clearly labeled with hazard symbols, batch number, and purity grade. Documentation traces back each container to its production date and lot so anyone who needs to reference an analysis certificate has that information ready. Standard grades reach 98% purity or greater. The labeling notes not just the molecular formula (C3H9BrOS) but also the correct UN shipping code due to its chemical classification. In my own lab days, I learned to trust suppliers who gave up-to-date safety data sheets and calibration standards for each shipment, which prevented missteps in measuring out reactions or confusing similar-looking reagents.

Preparation Method

Classic preparation involves reacting trimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) with methyl bromide under controlled cooling. The methylation step must be done behind a fume hood, with proper carbon filtration, because methyl bromide proves hazardous on its own. The reaction typically yields a solid slurry, which gets filtered, washed, and sometimes recrystallized from ethanol or acetone until pure. This remains a prime example of chemistry where yield depends as much on temperature control as on reactant purity. Excess methyl bromide gets scrubbed with potassium permanganate solutions—no one wants that vapor lingering where people work. The most successful syntheses I’ve seen focus on thorough drying before packing up the finished salt, or you end up with a sticky mess rather than crisp, flowable crystals.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

The main draw for trimethylsulfoxonium bromide lies in its ability to act as a methylene transfer source. Treating it with base, often sodium hydride, creates a sulfoxonium ylide—a short-lived, highly reactive species that inserts into carbonyl bonds. Chemists use it to make epoxides from aldehydes or ketones; this method sometimes beats traditional peracid routes in efficiency, especially with sensitive or highly functionalized starting materials. Its versatility means researchers have developed dozens of modifications: swapping the methyl arms for larger alkyls changes selectivity, altering the sulfoxonium core opens new paths for catalysis or ligand design. I’ve met synthetic chemists who swear by this compound for handling stubborn ring-forming steps, all because the ylide is tame compared to phosphorus ylides and leaves fewer messy byproducts.

Synonyms & Product Names

In shops or online catalogs, this salt might show up as trimethylsulfoxonium bromide, methylation reagent, TMSO bromide, or simply as a sulfoxonium salt. Chemical abstracts register it under numbers like 1774-47-6. Bigger suppliers put their own product codes on it, but most practicing chemists will recognize it from its functional groups and classic crystalline form. Academic papers sometimes abbreviate its name, but if you look at the reaction summaries or spectral data, the key identifiers like melting point or molecular weight always give it away. Suppliers like Sigma-Aldrich or Alfa Aesar keep it on hand in both small and bulk packaging.

Safety & Operational Standards

Working with trimethylsulfoxonium bromide calls for gloves and eye protection as a baseline. Even though the powder itself gives off no obvious fumes, dusting during weighing or transferring can irritate the nose and throat. Chemical hygiene rules recommend using a lab coat and not trusting any open dish on a crowded bench. Emergency protocols need to cover possible methyl bromide exposure during synthesis or clean-up, as well as procedures for spills or exposure. Disposal runs through designated organic waste containers, not down sinks or general trash. I’ve known teams who regular revisit their safety protocols, especially after synthesis scale-ups, because large batches raise the risk that something gets overlooked—a lesson learned more than once in busy labs.

Application Area

The heart of trimethylsulfoxonium bromide’s popularity stands in organic synthesis. Labs use it for epoxidation of carbonyls, especially in building blocks for pharmaceuticals or advanced polymer precursors. It’s a go-to tool for medicinal chemists shaping new ring systems or tweaking molecular frameworks to adjust drug activity or physical stability. Material scientists have explored its use in surface functionalization steps—sometimes adding just enough reactivity to modify optical polymers or electronic substrates. Analytical chemists sometimes use it as a methylation agent or for assembling stable isotopic tracers. Over the past decade, more chemical manufacturers have found ways to tune processes using this reagent, instead of riskier options like diazomethane. I’ve talked to university researchers who view it as a reliable bridge between basic research and practical manufacturing-level chemistry.

Research & Development

Studies have not stopped at the classic epoxidation reaction. Researchers keep searching for new variants, like using enzyme-compatible conditions or greener solvents to run reactions. Teams have explored tuning the methylation pattern or swapping in new substituents to develop asymmetric versions, hunting for ways to steer synthesis toward single enantiomers. I’ve seen presentations where postdoctoral researchers shared findings on new ligands derived from sulfoxonium salts, aimed at catalysis in metal complexes. Major industry players sometimes fund studies to compare toxicological profiles or environmental persistence compared to long-used reagents.

Toxicity Research

Toxicity studies show that trimethylsulfoxonium bromide does not present the severe hazards of some long-lived solvents, but it should never be taken lightly. Inhalation of dust or skin contact causes irritation, and accidental ingestion poses health risks. Animal testing in the past defined safe exposure limits for short-term contact, but regulatory bodies still push for more data on chronic exposure and environmental release. It does not appear to bioaccumulate rapidly, but breakdown products require separate assessment, especially for wastewater disposal following manufacturing-scale synthesis runs. Risk minimization, whether through engineering controls or personal protective equipment, remains the rule. I’ve talked with industrial hygienists who emphasize the need for regular air monitoring when handling methyl bromide precursors—a detail too often skipped until an accident forces change.

Future Prospects

Trimethylsulfoxonium bromide’s appeal continues growing as green chemistry initiatives demand cleaner, more predictable reagents. Newer process developments look to cut down on waste, and the byproducts from this salt usually end up easier to manage than older epoxidation agents. Expectations run high that improvements in atom economy and asymmetric catalysis will draw in even more industrial users. University labs have started incorporating derivative research into advanced organic synthesis curriculums, reflecting rising interest in alternatives to transition-metal reagents. As environmental scrutiny encourages development of safer reagents and milder activation conditions, trimethylsulfoxonium bromide stands poised to remain a mainstay for both exploration and efficient production in the chemical world.

Why Chemists Reach for Trimethylsulfoxonium Bromide

Trimethylsulfoxonium bromide doesn’t turn up on grocery lists, but it has a reputation among chemists for how it simplifies tough problems in synthetic organic chemistry. This compound enters the lab as a white or off-white powder and does its work quietly, yet its fingerprints are all over a lot of significant discoveries and daily industrial processes. My first experience with it came in graduate school, on a night where the air in the lab mixed up smells I still haven’t forgotten. We used trimethylsulfoxonium bromide to make epoxides—those three-membered rings that show up in medicine, plastics, and even pesticides.

Inside the Toolbox of Modern Organic Chemistry

The simplest explanation: this substance is a methylating agent—an ingredient that helps move a methyl group (one carbon surrounded by three hydrogens) onto another molecule. You can’t always pull this trick off with just any chemical. Some methylators cause explosions, or they kick off toxic fumes that threaten everyone in the room. Trimethylsulfoxonium bromide, compared to its rowdier cousins, lets you work with fewer risks.

Where it really shines is making epoxides through the Corey-Chaykovsky reaction. By mixing trimethylsulfoxonium bromide with a strong base, you get a ylide (a molecule full of chemical tension), ready to react with carbonyl compounds. This turns aldehydes and ketones into epoxides, molecules that bend and twist their way into so many pharmaceutical and industrial products. If you’ve benefited from modern drugs or special coatings that resist corrosion, there’s a decent chance trimethylsulfoxonium bromide was hiding somewhere in the supply chain.

Why Safety and Care Matter

Lab safety lessons rarely skip over trimethylsulfoxonium bromide. On the surface, it doesn’t seem fierce, but enemy lists in lab manuals warn that it brings some toxicity risks, especially to the skin and respiratory system. Some researchers, myself included, still remember the first time they cracked open a bottle and felt the sting at the back of the throat when caution slipped for just a moment. Smart managers keep it locked away and only trusted hands measure it out. Gloves, goggles, and fume hoods aren’t just suggestions when dealing with it.

Trimethylsulfoxonium Bromide in Industry

Scaling a reaction from small academic vials to a plant’s reactors never goes smoothly, but trimethylsulfoxonium bromide has proven itself as a reliable workhorse outside university walls. It helps smaller specialty chemical makers produce materials for life-saving medicines, advanced polymers, and even agrochemicals that push crop yields higher. It does all this without the same pyrotechnics or health scares that accompany some of the old-school reagents.

Not every chemistry teacher brings up the supply chain headaches. Factories need steady, pure shipments, and raw material sources do not always run smoothly. Chemists have learned to audit their vendors and implement backup plans. My old lab always kept a little stockpile “just in case,” after an unexpected delivery delay nearly derailed a month’s worth of experiments.

Rethinking the Future

Trimethylsulfoxonium bromide isn’t perfect. Handling it demands respect. There are whispers in academic journals about greener alternatives or improved processes that could cut back on waste and worker exposure, but research takes time and commitment. If manufacturers and scientists share knowledge, invest in training, and keep updating protocols, better and safer methods won’t be far behind. For now, trimethylsulfoxonium bromide keeps its spot as a problem-solver in labs where precision and reliability count for everything.

Understanding the Risks First

Anyone who’s worked with Trimethylsulfoxonium Bromide (TMSB) in a lab knows it demands respect. I’ve handled this commonly used alkylating agent in organic synthesis more times than I can count. TMSB doesn’t explode at the drop of a hat, but it can catch less careful chemists off guard. It hits both the skin and lungs with irritation, and its dust doesn’t belong anywhere near your eyes.

Practical Steps for Protection

Safe lab habits start with gear. Gloves rated for chemical resistance should go on before you even open the bottle. Disposable nitrile or neoprene gloves keep direct contact out of the picture. Don’t skimp on this step: even quick skin contact feels bad and gets dangerous fast. Add a lab coat—preferably one snapped all the way up—and close-toed shoes to block splashes. Safety goggles shield your eyes from dust or accidental sprays, especially during transfer or weighing.

Once you dress right, work in the right place. Open containers in a fume hood; this isn’t negotiable. TMSB forms dust that can become airborne with barely a nudge. Breathing this in makes for a rough day (or worse). Hoods pull it away from your face and everyone else’s. If a hood isn’t available, step back and question whether you should go ahead at all.

Keeping the Work Area Safe

Organization saves more than time—it prevents injuries. Clean, uncluttered benches limit accidents. I always keep the only needed tools inside the hood and move any extras out. Keep material sealed tight in its original bottle with accurate labeling. Do not leave this chemical open; accidental spills or mix-ups in unlabeled bottles have real consequences, including chemical reactions you never intended to start.

Dry material can build up on balances and spatulas. Wipe these up right away, wearing gloves and using a wet disposable towel. Wash glassware immediately after use. Never let residues sit around; old, forgotten TMSB might break down in unpredictable ways. Store fresh material away from heat, moisture, and sources of ignition. Heat is the enemy here, since this chemical decomposes, releases noxious fumes, and creates dangerous pressure if sealed without ventilation.

Reacting to Spills and Accidents

No matter how much you plan, spills happen. I’ve seen TMSB dust end up across a benchtop more than once. Don’t panic. If it hits the skin, wash thoroughly with soap and water. For larger releases, cover the powder with damp towels to keep the dust down, scoop up carefully, and place everything in a sealed chemical waste bag. Always report accidents, even minor ones, because someone down the line might encounter leftover contamination.

For eye contact, go straight to the eyewash and rinse for at least fifteen minutes. Inhalation calls for fresh air right away. Chronic exposure risks aren’t well-studied, so err on the side of caution every time.

Building a Culture of Safety

Safe handling doesn’t just protect the user; it shields everyone sharing the lab or building from exposure. Training goes a long way—don’t assume new labmates know all the steps. If I bring a new student into the workspace, training covers TMSB and every chemical with comparable hazard potential. We use standard procedures and reinforce them daily. Rushing or taking shortcuts leads nowhere good.

Knowledge, vigilance, and clean habits form the backbone of chemical safety. Those who work with TMSB owe it to themselves—and their teams—to treat every session as if safety matters most, because it always does.

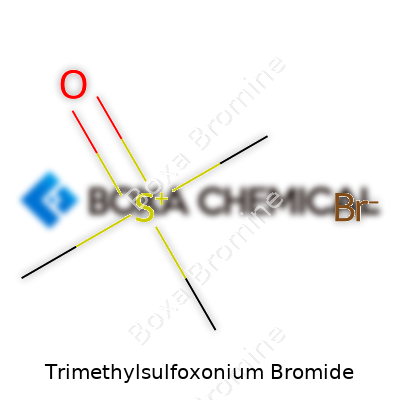

Chemical Formula and Structure

Trimethylsulfoxonium bromide stands out among laboratory reagents for its clean, sharp molecular design. The formula, C3H9BrOS, reflects three methyl groups attached to a sulfoxonium center, balanced by a bromide ion. Shorthand chemists use: (CH3)3SOBr. Its structure isn’t a tangled web—picture a sulfur atom in the middle, a double bond connecting to oxygen, three extensions for the methyl groups, then the sulfur tagging along with a full positive charge, overall balanced by the bromide counterion. That configuration channels much of its unique chemical energy. It’s both simple enough for students to sketch fluently and reactive enough to star in advanced syntheses.

Importance in Synthesis

Years back, as a student sweating my way through organic chemistry, I learned firsthand the difference between an abstract reagent and a tangible, powdery chemical you can hold and spill on the benchtop. Trimethylsulfoxonium bromide isn’t just a name in a book. Its strong leaving group tendency comes from that positively charged sulfoxonium, which doesn’t just sit around. In real labs, scientists rely on it for the Corey–Chaykovsky reaction—a process that transforms carbonyl compounds into epoxides or cyclopropanes. A graduate student might glance at their results and sigh with relief, knowing that this solid white salt delivered on its chemical promise.

Making molecules is like building with blocks, and not every block fits everywhere. Reagents like trimethylsulfoxonium bromide let chemists expand their toolkit, filling in crucial gaps. This isn’t about theoretical elegance—it’s about tangible progress for research. Even outside academic circles, pharmaceutical startups and specialty chemical companies find a use for this compound, especially because it works under relatively mild conditions, reducing the environmental and safety risks that harsher chemicals bring.

Safety and Handling

Working with any chemical carries a duty not only to personal health but also to anyone in the room. Bromide salts don’t always smell or seem dangerous, but accidental contact can be a rude awakening. Anyone handling trimethylsulfoxonium bromide must wear gloves, goggles, and work in a ventilated space. It’s not just about following rules for the sake of rules. You reduce accidental contact, accidental inhalation, and allergic reactions. Years of lab experience have taught me that a few minutes spent on basic safety means hours saved avoiding medical problems. Incidents hurt reputations and stall projects; proper handling keeps everything on track.

Addressing Current Challenges

Some companies face steady pressure to cut chemical waste and step up sustainable practices. Trimethylsulfoxonium bromide helps because it promotes specific reactions that generate less waste compared to more aggressive alternatives. Factories can scale up these reactions without bottles of hazardous byproducts clogging up the disposal chain. For labs trying to stay ahead of regulatory changes, switching to protocols based on more selective reagents helps meet newer, tougher standards. Suppliers should communicate purity, shelf life, and recommended storage to support consistent, reliable outcomes.

Looking Forward

Access to clear chemical information empowers everyone—students, researchers, and industry veterans—to use reagents like trimethylsulfoxonium bromide responsibly. As education and communication improve, more people recognize how the right chemicals push boundaries, not just in textbooks but in the everyday grind of discovery and innovation.

What It Means to Work with Trimethylsulfoxonium Bromide

Trimethylsulfoxonium bromide shows up in the lives of organic chemists far more than most people would guess. Its role as a methylation agent means it sits on the shelves of labs that are constantly pushing to build molecules with precision. Like a lot of synthetic tools, this white powder demands respect. Take it lightly and trouble won’t be far behind.

Getting Storage Right from the Start

Trouble often starts with taking shortcuts on storage. Moisture and direct light will chew through a bottle of trimethylsulfoxonium bromide in weeks. Any chemist who’s seen trace water creep into a vial knows the slow ruin that follows—a change in texture, a whiff in the air, then uncertainty about purity. Each time, it’s a reminder: airtight containers earn their keep in the lab. Thick glass, a PTFE-lined cap, and a clear label set you up for success.

Temperature Matters More Than Many Admit

Some chemicals tolerate a bit of warmth. Trimethylsulfoxonium bromide does not. A day on a sunny bench can shift it from safe to sketchy. I learned to keep bottles in a dedicated cool, dry cabinet—ideally, a desiccator filled with fresh silica gel. If your lab swings with the seasons, choose a spot far from radiators or sunny windows. No one wants to guess what’s gone wrong during a failed reaction, only to piece together that heat exposure was the thief.

Why Air Kills Confidence

Oxygen and humidity punch holes in reliability. Fasteners loosen, gloves and scoops go missing, someone forgets to recap. Before long, that bottle you trusted doesn't deliver methylations with the same snap. Without strict habits—gloves on, cap sealed, scoop bone-dry—yards of experiment notes go to waste.

Human Habits Save More Than Labels Do

The best storage setup still relies on ordinary routines. New students might keep trimethylsulfoxonium bromide in the wrong drawer, tucked between pH paper and Parafilm. Even experienced hands can rush cleanup at the end of a long day. Locking away these powders—always in the same spot, behind a chemical safety sign—breeds predictability. In my first year, I treated every vial as gold, and labs that keep that attitude re-test fewer batches.

Fire Isn’t Just a Distant Threat

Trimethylsulfoxonium bromide doesn’t ignite easily, but it releases toxic fumes if it does. This risk becomes real if a lab doubles as a storage closet for acids and oxidizers. Those labels—“keep away from incompatible substances”—aren’t just filler. Fireproof cabinets, clear chemical separation, and fire extinguishers at arm’s reach put distance between a small mistake and real loss.

Forward Steps to Fewer Accidents

Routine audits, refresher training, and buddy systems help keep storage practices sharp. Labs with good habits spot swelling bottles, faint smells or stray powders right away. I haven’t forgotten the panic when a senior chemist opened a bottle that hissed back—some moisture had gotten in. We dumped it, refreshed our protocols, and kept safety in the spotlight. Storing trimethylsulfoxonium bromide never takes that much gear or time, but it pays back every hour spent right.

References

- PubChem, National Institutes of Health. “Trimethylsulfoxonium Bromide.”

- Sigma-Aldrich. “Safety Data Sheet: Trimethylsulfoxonium Bromide.”

- Prudent Practices in the Laboratory, National Academies Press.

Looking Beneath the Lab Labels

Sitting behind fume hoods and lab benches for years, I’ve poured enough chemicals to know the number stamped on a container matters a lot. Trimethylsulfoxonium bromide pops up on plenty of synthetic routes — from epoxidation tricks to the odd niche application. Most chemists reach for this white crystalline powder trusting the label, but not everyone thinks twice about what “purity” means beyond a few digits and a percent sign.

Usual Purity Offered and Why It Matters

Suppliers routinely offer trimethylsulfoxonium bromide at purities of 98% or higher. The industry standard floats around 98-99%, and some provide HPLC or NMR documentation to back it up. That remaining 1-2% might not seem much, but I’ve run into batches where even this small chunk led to extra spots on TLC or strange peaks in spectra, especially during scale-up. For those doing small-scale or routine methylidene transfers, the minor contaminants often don’t derail things, but anyone working on a process that demands repeatable, clean yield learns to watch those details like a hawk.

The big chemical distributors—Sigma-Aldrich, TCI, Alfa Aesar, Acros—push the high-90s percentage. This level gets most academic research done without fuss. Scale-up for pharma or specialty materials pulls from the same pool, but there, QA crews run their own checks and spike in controls since regulatory demands cut no slack. Grubb’s type reactions or Williamson syntheses don’t leave much room for noisy byproducts, so the difference between 98.0% and 99.5% can show up in final purity and yield. You discover the headaches only after someone on the team pipes up: “Why did the NMR baseline shift after switching suppliers?”

Impurities: More Than Just Numbers

Ignoring impurity content now often leads to costly rework later. Common issues with trimethylsulfoxonium bromide include trace sulfoxides, moisture, or color arising from unstable light exposure. These sneak in from either sloppy synthetic conditions during manufacture or bad storage before the stuff lands in your hands. In sensitive reactions, the risk from water content or residual solvent can stall a project. I’ve had a box delivered where humidity leaked in: the batch didn’t just cake, it ruined a week of work. Labs running critical syntheses tend to double-bag and stick desiccants in—learned that one hard way too.

How To Cut Risks, Boost Certainty

Savvy researchers grab more details from suppliers before buying. Good vendors provide recent chromatography or NMR, not just the blanket "98% min." A quick scan or certificate of analysis stops most surprises in their tracks. In our group, we've tossed in a test solubility or run a dry NMR before launching into a weeklong multistep procedure. It saves time and sanity later.

Anyone working with intricate synthesis—or thinking of publishing reproducible results—keeps a habit of logging batch numbers and storage conditions. Returning to a trusted supplier pays dividends in reliability. If purity above 99% is critical, a handful of specialty shops will guarantee it, sometimes for a steep markup. The investment buys cleaner baselines and fewer late-night troubleshooting sessions. Relying on strong, transparent supplier documentation and tried-and-true storage methods turns that “98%” figure into something you can actually believe in.