Dichloroethane: From Discovery to Today’s Chemical Industry

Historical Development

Dichloroethane, often called 1,2-dichloroethane or ethylene dichloride, first turned up in chemists’ laboratories in the early 19th century. Back then, scientific curiosity often ran ahead of safety. Michael Faraday, a true pioneer, produced it by reacting ethylene with chlorine. Decades rolled on, and industry found out that this compound could open doors in plastics, fuels, and solvents. Vinyl chloride production eventually locked dichloroethane into its key role, helping shape everything from PVC pipes to furniture. The development tells a story where curiosity led to widespread practical use, with society learning—sometimes painfully—how to harness and regulate potentially hazardous chemicals.

Product Overview

Dichloroethane sells as a clear, colorless liquid. Few other chemicals take on so many hats in manufacturing. It shows up as an important intermediate in making vinyl chloride, essential for polyvinyl chloride (PVC) plastics. Beyond that, it has a run as a solvent, a degreaser, a chemical extraction agent, and even an ingredient in some adhesives and cleaning formulations. Numerous industries, from plastics to pharmaceuticals, rely on it to carry out specialized chemical transformations.

Physical & Chemical Properties

Every technician who has handled dichloroethane notices its pleasant yet strong chloroform-like odor. Boiling at 84°C, this moderately volatile liquid evaporates more intensely at room temperature than water. It mixes poorly with water but dissolves most organic compounds with ease. With a molecular formula of C2H4Cl2 and a molar mass of 98.96 g/mol, dichloroethane takes to chemical synthesis like few other solvents. It resists degradation at room temperature, stands out with its density of 1.25 g/cm³, and its flammability rating pushes people to store it away from spark sources.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Chemical suppliers handle dichloroethane with care, labeling each container with hazard symbols and regulatory markers. Each shipment states the chemical’s grade, purity level—often upward of 99% for industrial purposes—and impurities profile. The labeling comes packed with safety instructions, including the Global Harmonized System (GHS) identifiers for flammability, acute toxicity, and environmental hazard. Material Safety Data Sheets supply clear data on boiling point, flash point, storage recommendations, and steps for dealing with spills or accidental exposures.

Preparation Method

Factories mostly synthesize dichloroethane by passing ethylene gas and chlorine together in a controlled reactor. This “direct chlorination” method, pioneered in the mid-twentieth century, runs under strict temperature and pressure limits. By adjusting catalytic conditions, producers boost yield and suppress unwanted byproducts like hexachloroethane. An older process—oxy chlorination—mixes ethylene, hydrochloric acid, and oxygen, with a copper chloride catalyst. It’s worth remembering that modern plants keep environmental release as low as possible, recycling byproducts to cut waste streams and reduce toxic exposure for workers and communities nearby.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

Dichloroethane’s carbon-chlorine bonds serve as reactive handles for chemists. In the lab, it transforms into vinyl chloride using thermal cracking—a reaction central to global plastic production. It also acts as a starting point for various transformations: forming ethylene diamine, chlorinated solvents, and other specialty intermediates. Its solvent power accelerates nucleophilic substitution and elimination reactions, crucial for producing pharmaceuticals and custom chemicals. Its reactivity can also yield potential environmental byproducts, pressing research labs and factories to refine reaction conditions for safer, lower-emission outcomes.

Synonyms & Product Names

Dichloroethane carries an assortment of aliases, including ethylene dichloride, 1,2-dichloroethane, and EDC. Industry product names sometimes reflect trade branding, but chemical registries and regulators point to the CAS number 107-06-2 for clarity. These synonyms turn up on safety labels, shipping documentation, and technical purchase orders across continents. Chemists and logistics crews stick with these names to avoid confusion, especially in multinational settings where consistent labeling can make the difference in emergency response and safe handling.

Safety & Operational Standards

No one who works around dichloroethane forgets its potential hazards. Even short-term exposure can cause irritation of the eyes, nose, and throat. High doses take a toll on the liver and kidneys. Regulatory agencies—including OSHA, NIOSH, and the EU’s REACH program—cite strict occupational limits and set protocols for ventilation, spill response, and personal protective equipment. The chemical ranks as flammable, pushing safety officers to mandate spark-resistant handling tools and continuous air monitoring in larger plants. Emergency showers and eyewash stations form part of the built environment where this compound is stored or manipulated.

Application Area

Nearly all the world’s dichloroethane ends up in PVC production plants, turning into vinyl chloride and then flowing into downstream uses—pipes, siding, flooring, and cable insulation fill out daily life. Laboratories that need a reliable solvent for grease, wax, resins, or oils will sometimes turn to this compound, though safer substitutes now get priority. A shrinking slice still goes toward chemical extraction, adhesives, and pharmaceutical intermediates, with regulatory changes slowly nudging industry to seek alternatives based on safety and environmental impact.

Research & Development

Few chemical sectors pour as much effort into life-cycle studies as those involving dichloroethane. In my years working alongside chemical engineers, I’ve watched research labs test new synthesis routes designed to break away from the need for toxic feedstocks. Green chemistry approaches, such as using renewable sources or catalysts that minimize harmful byproducts, get growing attention. Scientists keep testing improved scrubbers and wastewater treatments that neutralize trace releases, hoping to avoid both acute poisoning cases and subtle long-term risks linked to soil and groundwater contamination.

Toxicity Research

Studies tracing back to the mid-1900s detail how dichloroethane’s vapors, when poorly controlled, cause headaches, dizziness, and even narcosis in poorly ventilated environments. Research on rats and mice connects long, chronic exposure with a rise in certain cancers. Toxicologists from health agencies regularly review workplace exposure limits, refining standards based on the most recent data. Public health studies in high-production areas point to spills leaking into local water tables, risking localized cancer clusters, and raising questions about long-term stewardship. These findings press for further monitoring and ongoing investment in cleanup technologies.

Future Prospects

The future of dichloroethane hangs in a balance. There’s clear demand for its role in PVC, an irreplaceable staple for affordable housing, medicine, and infrastructure worldwide. At the same time, tighter health and environmental standards push chemical makers to cut accidental releases and look for safer substitutes. The next generation of chemists aims to design molecules and processing aids from safer, renewable ingredients, chipping away at the need for persistent, toxic intermediates. Investments in emissions control and greener plant technologies show promise, but the transition will take years as both infrastructure and habits slowly shift. Experience has taught the industry to blend innovation with caution—real progress depends on pushing the conversation forward with facts, transparent research, and a willingness to keep safety front and center.

A Chemical With Reach

Walking through any industrial hub, you’ll find chemicals that barely enter public conversation but shape much of the modern world. Dichloroethane, also called ethylene dichloride, is one of these quiet giants. Factories use it far from everyday headlines, but traces of its reach land in countless corners of daily life.

Vinyl Chloride Starts Here

For years, I never realized the stuff behind my shower curtain or the pipes tucked inside the walls began in a chemical plant with something as unassuming as dichloroethane. Heating dichloroethane with other ingredients produces vinyl chloride, the base for PVC plastic. Without this reaction, a lot of things—from water pipes underground to blood bags in hospitals—would not exist. In 2020 alone, plants pumped out millions of tons, fueling construction, medicine, and more.

Solvents and Industrial Uses

Industrial processes love solvents, especially those that can break down grease, tar, and tough resins. That’s where dichloroethane steps up again. It plays a job supporting the production of cleaning agents, adhesives, and even certain paint removers that pull old stains off metal or machinery.

Back in the day, small metal shops used such solvents as a quick way to wipe parts clean. Today, regulations tighten down on this because of the risks to both workers and anyone living nearby. Yet, industries dependent on old machines or dealing with heavy grime turn to tried-and-true helpers like this chemical.

Risks and Realities

Knowing where these chemicals end up makes you look harder at costs the average person doesn’t see. Dichloroethane doesn’t break down quickly if it escapes into water or soil. It can seep into groundwater that feeds wells and supplies towns. People who live near major industrial areas face greater chances of encountering it, especially if there’s ever a spill or leak. Health studies connect long-term exposure to problems like liver or kidney damage and higher cancer risk.

Actually, using this chemical in places with less environmental oversight means entire communities can face higher risks. It’s hard to ignore stories from folks living downriver from chemical plants, where fish and tap water start to show trace amounts, and sometimes government oversight lags behind reality.

Better Practices and Innovation

Manufacturing doesn’t turn on a dime, but plenty can be done. Tightening how companies store and handle dichloroethane can prevent a lot of trouble. Sensors and double-walled tanks catch leaks early. Switching to safer alternatives in products like paint removers reduces exposure outside controlled plants.

Transitioning industry means retraining workers, retooling equipment, and sometimes even rethinking supply chains—tasks that take money and leadership. If public health matters as much as profits, investing in these changes pays back in fewer hospital visits and cleaner neighborhoods.

Demand for PVC and fast-acting solvents isn’t falling off any time soon. As long as society leans on sturdy plastics and quick cleaning solutions, dichloroethane will stick around. The questions that matter most focus on who faces the risks, who profits, and how responsibly companies can act. Having spent years talking with both workers inside plants and families living nearby, I’m convinced solutions start with honest conversations and strong oversight.

The Real Risks of Dichloroethane

Ask anyone who’s worked with chemicals about dichloroethane, and the warnings come out quick. This colorless liquid, often used in making vinyl chloride, carries some dangers most people don’t realize. Inhalation knocks a person back with symptoms that hit in less than a few minutes—dizziness, drowsiness, nausea, and sometimes unconsciousness. Breathing this stuff, even for a short time, puts real stress on the brain and the liver. Studies from workplace exposures show that chronic contact messes with the nervous system and brings long-term health consequences.

Deeper Than Just Acute Effects

The stories I’ve heard from those working around dichloroethane match up with what the facts say. A small spill in a closed area led to two workers needing medical help for loss of coordination and headaches that lingered for days. Science digs deeper and points to the real worry: increased risk of cancer. The International Agency for Research on Cancer classifies dichloroethane as possibly carcinogenic to humans. Enough lab research finds it boosts cancer chances in animals, raising questions about its effect in people, especially with repeated exposure.

Everyday Exposure Is Still a Concern

Dichloroethane isn’t just locked away in chemical plants. Old cleaning products, adhesives, and even some personal care items used to contain it. New laws phased most of this out, but pipes and old stock in basement shelves could still bring contact. The smell lingers, and it evaporates fast—sudden headaches or irritation can be a telltale sign. EPA sampling sometimes picks up trace amounts in groundwater where factories dumped waste long ago. One study in the U.S. found dichloroethane in the drinking water of several homes near industrial sites. Not everyone will experience immediate symptoms, but the long-term risks stack up slowly.

Worker Safety and Community Protection

Job sites using dichloroethane have a duty to keep workers safe. I’ve seen the difference proper training and equipment make. Open windows, working fans, and good ventilation systems cut down on the fumes that cause danger. Gloves and face masks provide a barrier for skin and lungs. Simple steps like having spill kits and showers nearby save lives in an emergency. Under OSHA rules, any workplace with possible exposure needs safety plans and regular air testing.

Reducing the Threat in Homes and Neighborhoods

Communities near factories or waste sites carry the most risk from old contamination. It’s not enough just to test air and water once a year. Local governments must keep testing regular and share results openly. Cleanup projects help, but public awareness plays an even bigger role. I always urge people to check old storage areas, avoid old solvents, and keep contact information for poison control close at hand. Health agencies suggest running tap water for several minutes in the morning if living near a known site. Addressing leaks and spills fast reduces both health and environmental impact.

Clearing the Air: Public Responsibility Counts

Cutting down on dichloroethane exposure saves lives. Every worker deserves strong protections, and every neighborhood should have clean air and water. By knowing the risks and pushing for safer practices, people and organizations can protect themselves and their communities. Future generations shouldn’t have to deal with the fallout from decisions made decades ago or chemicals hiding in plain sight.

Why Bother with Special Storage?

Dichloroethane, also known as 1,2-dichloroethane, shows up in the chemical industry for a reason—it’s a hardworking solvent and a building block in making many plastics and chemicals. But this clear, sweet-smelling liquid is no harmless bystander. It brings risks like toxicity, flammability, and the threat of leaks that can endanger people and the environment. In my years learning about industrial chemical safety, ignoring proper handling always came back to bite people—health scares, fines, and worse. So, getting the storage right isn’t red tape. It’s about safety and peace of mind.

Physical Dangers You Can’t Ignore

Dichloroethane can catch fire, and when it mixes in the air at the right levels, all it takes is a spark. Its vapors spread fast, building up in low spots and surprising anyone nearby. Breathing in even small amounts can lead to headaches, dizziness, and long-term health trouble. Liquid spills threaten water sources and local wildlife.

The chemical eats away at plastics and rubbers that aren’t compatible, and it can corrode certain metals over time. Ordinary containers break down or leak, especially under sun, heat, or pressure changes you find in a busy warehouse or production yard. I’ve seen warehouses where ordinary drums failed in a matter of months because someone skipped their homework about these details.

Picking the Right Containers

Steel drums with inner linings, solidly welded seams, or high-density polyethylene tanks handle dichloroethane better than bargain-basement options. I always ask suppliers for compatibility certificates before signing purchase orders, just to cut out nasty surprises. Going with just any drum, or trusting some “chemical-resistant” marketing claim, simply isn’t worth it.

Seals and gaskets need attention, too. Teflon or Viton stand up much better than cheaper rubber, which goes mushy and lets leaks slip by. Regular inspection routines—at least once a week if you’re handling lots of product—catch small leaks before they turn serious.

Temperature, Light, and Ventilation

Dichloroethane stays more stable in cool, dry, dark places. Direct sunlight or high warehouse temperatures push up pressure inside sealed drums. That leads to swelling, risk of bursts, or, over time, dangerous vapor releases that can accumulate unnoticed. A ventilated room keeps vapors from getting trapped. Even small fume build-ups inside a storage shed can reach hazardous levels before anyone smells a thing.

Industry rules recommend temperatures below 27°C. I’ve seen operations where temperature stickers help catch small changes that may warn of a brewing problem. Don’t ignore climate—one hot, sticky summer day can shift chemical risks overnight.

Fire Safety Means More Here

Sprinkler systems, flame arresters on storage vents, and grounding straps for tanks cut the risk of explosions from static discharge or smoking. Firefighting foam and dry chemical extinguishers sit near doorways—water won’t do the job.

I always stress regular safety drills. Fast evacuation and knowing where spill kits and respirators are kept saves lives. You get one shot in a real emergency, so practicing isn’t a waste of time.

Training and Regulation

Workers need honest training about chemical dangers and safe handling from day one. Clear signs and locked rooms keep out unauthorized traffic. Sticking to OSHA, EPA, and local codes prevents fines and shutdowns. Full records of material amounts, inspection logs, and spill responses convince regulators that the operation runs responsibly, not just as an afterthought.

Big lessons come from real spills and mistakes—words in a manual come to life when you see the consequences unfold. Treating dichloroethane storage as a checklist item isn’t good enough. People and communities count on us to get this right, every time.

Understanding the Risks

Dichloroethane doesn’t have celebrity status like lead, mercury, or asbestos, but this stuff deserves respect. It looks like a clear liquid, has a bit of a chloroform scent, and carries a heavy load of risk for people and the environment. Working in a chemical plant for a summer job, I learned quickly that a spill can sneak up on you—one minute it seems manageable, next thing you know, folks are coughing, alarms are going off, and the scramble begins. Dichloroethane soaks into soil, threatens water supplies, and evaporates, making the air itself a risk if you breathe it in. Cancer risk lies at the core of the issue—over the years, the CDC, EPA, and World Health Organization have lined up to say chronic exposure can bring liver, kidney, and lung trouble, not to mention a bigger problem for the cells in your body.

Immediate Steps Count

Safety goggles and respirators shouldn’t gather dust in a storeroom. No fancy protocols matter if you skip that first moment: secure the area. People get curious, thinking "I’ll take a look," forgetting that vapors move fast and soak in through skin and lungs. Folks who worked in shipping back in the 90s still talk about the sharp odor after a hose popped on a tank. They cleared out fast, aired the place, then got the fire crew in with proper gear.

Next, stop the leak at the source. This part takes calm hands, teamwork, and muscle memory. In 2021, after a railcar leak in Texas, workers who knew their valves and emergency shutoffs limited spread in under fifteen minutes. They had practiced, not just skimmed the manual during coffee breaks. Fire crews have foam, blankets, and carbon pads ready to toss onto a spreading puddle. Waiting on slow-moving bureaucracy piles on more risk—chemical spreads, groundwater gets a hit, and families living close to the site get nervous calls that their drinking water could be off-limits.

Getting the Cleanup Right

Erasing a spill starts with containment. Dikes and booms aren’t high-tech, just tried and true—laying down absorbent socks or plastic berms on the ground gives responders extra minutes to suck up pooled liquid with vacuums or pump trucks. In Portland, after a warehouse tank rupture, hazmat crews raced to stop seepage into a storm drain. Any slipup gets pricey: one gallon missed in the drain can mean thousands spent filtering water and cleaning up miles downstream. The EPA has fined slow responders, sending the message that “good enough” doesn’t cut it.

After water, soil suffers next. Digging up affected earth, shipping barrels out for incineration, and monitoring the site for vapor is heavy lifting, but it beats exposing children and pets for years to come. Residents in upstate New York still resent the endless monitoring after a 2010 spill, but they remember that the alternative was worse—a slow drip of toxins poisoning well water.

Solutions for a Safer Future

Training does half the job; honest company culture does the rest. Plant managers and warehouse bosses who admit mistakes and push for regular drills make the difference. Technology helps—leak sensors, alarm integration, and better mobile equipment save time and lives. Companies now partner with universities to test new cleanup agents, pushing beyond the old “sand and shovel” routine. Most of all, factories near neighborhoods shouldn’t keep secrets. Alerting local fire departments, schools, and clinics builds real trust. In my experience, honest communication beats silver-bullet fixes every time.

No one aims to spill hazardous chemicals, but real preparation and direct action change the story from crisis to recovery. Protect the crew, respect the chemical, and keep learning from every close call.

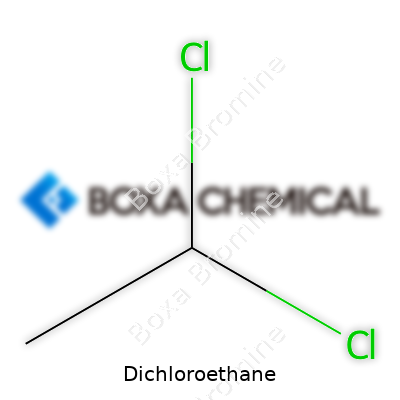

Understanding Dichloroethane in Everyday Life

Dichloroethane sounds like something locked away in a lab, but this compound plays a bigger part in modern life than most people realize. The formula for dichloroethane is C2H4Cl2. Strip it to basics, and you find two carbon atoms, four hydrogens, and two chlorines bonded in the chain. Some folks know it better by the name 1,2-dichloroethane, a nod to the way those chlorine atoms sit on the chemical backbone.

About the Chemicals We Use

Learning what’s inside everyday substances opens your eyes. Growing up in a house surrounded by farmland, chemical names became familiar early—my dad worked with pesticides, and the air sometimes filled with the sharp smell of solvents. Dichloroethane sits among those big-name chemicals; factories mostly use it to churn out vinyl chloride, the core ingredient in making PVC piping. Try picturing all the wires in your walls and that white plumbing under your sink—it probably started with C2H4Cl2.

The scope extends far beyond pipes and siding. This chemical plays a role in making cleaning agents, degreasers for metal parts, even in producing certain plastics and adhesives. Sometimes, curious minds wonder why these formulas matter. Knowing a chemical’s structure helps figure out its reactivity, safety risks, and where things might go wrong if misused. This is no trivial detail—handling or mislabeling substances leads to real accidents.

Health and Safety: Lessons Learned

Experience shapes your approach to chemicals. I remember hearing local news about an old warehouse in town that leaked barrels of tract chemicals into groundwater. Small compounds like dichloroethane last a long time in soil and water and cause harm to people. Long exposures link to problems with the liver, kidney, and even the central nervous system.

Reading facts isn’t enough—real stories hammer it home. One year during my college lab, a wrong pour led to a spill. Staff stepped in with gloves and fume hoods, no fuss, but the urgency was clear. Chemical formulas shouldn’t just stay on paper. People working in plants and students learning about chemistry need clear rules, proper labels, working ventilation, and honest risk discussions.

A Path Forward

Reducing harm starts with knowledge and respect. Industry can look for safer substitutes in production, such as bio-based alternatives for solvents. Governments hold a big stick too; I’ve seen regulations tighten to limit workplace exposure and keep waste from ending up where it shouldn’t. Public education plays a huge role. Folks deserve to know not just the formula of what’s nearby, but what it means for their health and environment.

C2H4Cl2 might seem like a dry chunk of data from a textbook, but its real-world footprint is heavy. Carrying this knowledge helps us all stay safer—and gives us a choice. From farms to factories to homes, understanding these formulas shapes decisions that last.