Dibromomethane: A Deep Dive into a Versatile Chemical

Historical Development

Dibromomethane has been around for decades, quietly making its mark across research labs and industrial sectors. Chemists in the early twentieth century began looking into halogenated methanes for new reactivity and useful applications. Soon enough, dibromomethane earned a spot because it opened up opportunities for synthetic pathways nobody had explored thoroughly before. Researchers didn’t stumble on it by chance but followed deliberate routes to understand the shifting balance between methyl halides. In my experience, conversations with experienced organic chemists often circle back to landmark papers published throughout the 1950s and 1960s as the source of foundational knowledge about dibromomethane’s chemistry, especially around the time when organobromine compounds saw expanded interest due to industrial chemical demand. The groundwork from those years still supports how people think about and handle the molecule today.

Product Overview

Dibromomethane, often known under its trade names like methylene bromide or methylene dibromide, appears as a colorless to faintly yellow, non-flammable liquid. You’ll run across it in everything from lab-scale synthesis to specialty manufacturing. Its slightly sweet, pungent odor gives it away in confined spaces, a feature that sticks with you after you’ve handled it even once. Chemists and process engineers value its mid-range reactivity compared to other haloalkanes, balancing manageability with potential for transformation.

Physical & Chemical Properties

Physical details for this molecule pack plenty to consider at the bench or on the plant floor. Its boiling point sits near 97°C, making it more volatile than you might expect from a molecule this dense, with a specific gravity over twice that of water (2.49 at 20°C). Exposure to air results in slow evaporation, although not enough to make containment a nuisance for short procedures. Water solubility stays low, just 2.6 g/L at 20°C, but its organic compatibility opens up a world of solvents. The refractive index clocks in at 1.54—worth knowing for quality tests. One notable item from my own lab days: it resists attack by strong bases but reacts generously with nucleophiles, keeping it from lingering in systems designed around harsh alkaline washes.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Commercial sources label dibromomethane according to precise CAS registration and UN transport regulations, usually using “98%” or “99%” as purity benchmarks. Genuine bulk containers brag about low water and acid content for customers who demand tightly controlled side reactions. Each drum or ampoule often arrives with certificates tracking batch number, analytical methods (such as GC or NMR trace), and hazard pictograms required by the Globally Harmonized System (GHS). From my own ordering experience, failure to check these tech sheets has tripped up more than one project, especially since even trace moisture could change a yield or sabotage downstream analysis.

Preparation Method

Industrial producers prepare dibromomethane by brominating methane or dichloromethane, though the old-school route—treating methylene chloride with elemental bromine under UV light—still yields a reliable product. The process starts with careful control of temperature and light, balancing reaction speed against unwanted formation of tribromomethane. Most modern plants adopt continuous-flow reactors with built-in monitoring for exotherms. After the reaction, fractionation purifies the dibromomethane, stripping out water, excess halogens, and byproduct trihalomethanes. Any chemist who has run this synthesis at scale knows its hazards: Overheating can turn a contained process into a runaway situation fast, especially if bromine vapors escape the system.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

Dibromomethane stands out because it behaves as a potent alkylating agent, primed to undergo nucleophilic substitution and even elimination reactions in competent hands. Its two bromine atoms act as leaving groups, which find frequent use in organic syntheses to introduce methylene bridges. Research teams exploit this in the creation of cyclopropanes or as a precursor to more complex carbene chemistry, especially through base-promoted reactions that eject both bromides. I’ve watched teams in medicinal chemistry push dibromomethane through elaborate routes just to lay down a key C1 building block. Its reactivity with Grignard reagents and amines provides routes to diverse small molecules, some of which anchor complex pharmaceutical scaffolds.

Synonyms & Product Names

Anyone digging through historical or supplier catalogs finds dibromomethane listed under a range of names: methylene bromide, methylene dibromide, and even the less common UN 2663 moniker for shipping. These variations can trip up new users, as older textbook protocols often refer to different nomenclatures. Global trade brings in variants of spelling or even non-English names, which resulted in one memorable incident at our warehouse—a shipment delayed for days because of inconsistency on customs forms. Rigor in product naming helps trace shipments accurately and improves lab safety, as the right label points to the right SDS and storage guidance.

Safety & Operational Standards

Dibromomethane poses specific hazards: moderate acute toxicity, irritant properties, and the risk of environmental harm if spilled. Storage guidelines favor cool, ventilated areas, sealed glass or specialized plastic containers, and strict separation from strong bases and reducing agents. Operations involving open handling call for gloves, goggles, and proper fume hood use. I recall one drill where a dropped flask set off room-wide alarms, leading to an evacuation that underscored how unexpectedly fast vapors can build up. Regulatory standards—OSHA, REACH, and GHS—mandate comprehensive training for anyone involved with the chemical. Regular audits and on-site monitoring address the risks, and the safety data sheets earn a second look every time a protocol changes.

Application Area

Researchers and engineers turn to dibromomethane in synthesis of pharmaceuticals, agricultural fumigants, and as a reagent for laboratory-scale reactions. Some legacy uses in soil treatment have faded due to regulatory action, but its role in specialty chemical manufacturing remains firm. In high-end resin and polymer production, its reactivity helps build up molecular weight or arch in custom linkers. R&D labs investigating carbenoid chemistry regularly rely on dibromomethane to access transient species for further development. I remember a collaborative project in artificial photosynthesis where dibromomethane served as a key intermediate, allowing multiple labs to converge on new catalysts.

Research & Development

Research into dibromomethane continues, with interest in both improving production efficiency and expanding its applications. Synthetic chemists keep pushing for greener, safer methods of preparation—photocatalytic bromination and continuous-flow innovation hold promise. In academia, studies probe the molecule’s behavior in tandem or cascade reactions, laying groundwork for new pharmaceuticals or materials. Industrial efforts look at waste reduction strategies, capturing byproducts for downstream use instead of sending them to incinerators. In several recent conferences, presenters shared advances in automation of dibromomethane dosing for combinatorial screening, underscoring both efficiency and safety.

Toxicity Research

Toxicologists have spent years evaluating the impact of dibromomethane on workers, communities, and ecosystems. Inhalation and skin contact both pose health risks, producing symptoms from mild headache to respiratory irritation and even central nervous system effects at higher exposures. Animal studies suggest potential organ toxicity with chronic handling. This research has already driven stricter exposure limits and vapor management protocols. Wastewater treatment systems at production plants have to trap and neutralize effluent before release. Personal experience with industrial hygiene consultants shows that ongoing monitoring and regular medical checks go a long way to protect teams.

Future Prospects

The future for dibromomethane ties into broader trends—chemical industry sustainability, demand for specialized building blocks, and ever-stricter safety regulation. Companies investing in advanced manufacturing control can cut emissions and broaden the molecule’s acceptance in more sensitive applications, including pharmaceutical synthesis. Startups and research centers keep looking at biocatalysis and renewable feedstock as possible foundations for new production routes. Tighter regulatory scrutiny in regions like the EU and California will shape where and how dibromomethane gets used, but for specialists, the molecule still holds promise as a reliable, versatile tool. Those keeping up with evolving standards and investing in rigorous safety have a clear path forward, drawing on both historical experience and emerging innovation.

What Is Dibromomethane?

Dibromomethane, also known as methylene dibromide, shows up as a colorless liquid with a slight, sweet smell. Chemists recognize its simple formula: CH2Br2. It doesn’t usually ring a bell outside laboratories, but it plays a bigger part in industry than most people realize.

Where Dibromomethane Ends Up

The first time I heard about dibromomethane, I was working alongside researchers looking into halogenated compounds. Factories use it for very specific reasons. One of the most notable places you find it is in the lab, as a solvent. Chemists choose it for reactions that call for a stable, non-flammable liquid, but its heavier weight compared to water comes in handy for things like density separation. Synthetically, it acts as a building block. The two bromine atoms let scientists swap pieces out to make other, more complex chemicals—think pharmaceuticals, dyes, or even pesticides.

My daily work brought me closest to dibromomethane during organic synthesis projects. It has unique reactivity: for example, important in the Simmons–Smith reaction, which helps build cyclopropanes—three-member rings found in drug molecules and natural products. This isn’t something you find in a household cleaner, but it makes major contributions behind the scenes in the world of medicine and material science.

Agricultural Connections

Dibromomethane can help control pests or act as a fumigant. It’s not a go-to product for the average gardener, but commercial growers have explored its use for soil and post-harvest treatments. Agrochemical companies have kept dibromomethane on their radar because it sometimes works where traditional pesticides fail, though regulatory bans have limited its use due to environmental concerns. No one wants brominated by-products finding their way into the groundwater, so careful handling is the name of the game.

Environmental and Health Concerns

Any story about a halogenated hydrocarbon would be incomplete without mentioning health. Exposure can irritate skin, eyes, or lungs. In the lab, double gloves and a fume hood aren’t suggestions—they’re rules. Long-term, there’s a possibility of serious health impacts, like other chlorinated or brominated substances. Local regulations keep an eye on emissions, disposal, and personal safety, not just to protect workers but the surrounding community too.

Brominated compounds build up in the environment more than people once thought. Studies suggest some break down slowly, traveling farther than anyone planned. This makes trace contamination a real problem, especially near manufacturing plants. Regular groundwater tests, tighter plant standards, and pressure on companies to rethink chemical waste have all grown out of problems spotted early with chemicals like dibromomethane.

Moving Forward—Safe Chemistry and Accountability

Safe handling begins with honest conversations in every workplace storing or using dibromomethane. Training new chemists always means running through safety data sheets and emergency plans. Factories follow strict disposal methods; research teams log their usage and waste. Regulatory authorities conduct routine inspections. These aren’t empty gestures—they reflect a hard-earned understanding of how one slip-up can contaminate, sicken, or even cause environmental scars that last decades.

Alternative methods for synthesis exist, though some companies drag their feet without clear incentives. Tackling the legacy of brominated wastes means supporting green chemistry, rewarding firms that pioneer cleaner solvents and adopting better controls for old substances. Dibromomethane has its place in industry, but giving it the respect it demands takes constant vigilance and a willingness to push for better solutions each year.

Everyday Hazards Lurk in the Laboratory

Dibromomethane doesn’t show up in most people’s kitchens or garages. Ask anyone who’s spent time in a chemistry lab, though, and they’ll recognize its sharp, distinct odor. It’s a colorless liquid, used in specialty chemistry and sometimes pops up during soil fumigation procedures. Not exactly a household name, but it’s out there.

The Risk Starts With Exposure

It doesn’t take much reading in chemical safety data sheets to realize dibromomethane isn’t something you want splashed on your skin or pouring down your throat. This stuff can irritate your eyes, skin, and lungs. Just a whiff could make your throat scratchy or leave you coughing. Nasty headaches and dizziness can hit if too much gets inhaled. Anyone who’s handled it without good gloves or a working hood will remember the burn.

What Science Says About Toxicity

Studies on animals point to real health concerns. Rats breathing in high concentrations ended up with lung and liver problems. In some cases, long-term exposure led to liver tumors. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency lists dibromomethane as a possible human carcinogen. It doesn’t get this label by chance; researchers noticed genetic damage in cells exposed to the chemical. That sets off alarm bells, even if studies on humans aren’t as clear-cut.

Beyond Laboratories: Environmental Notes

Dibromomethane made headlines decades ago as a byproduct of certain soil fumigants. Spills weren’t rare, especially before stricter regulations kicked in. Once poured on soil, some escapes into the air, while some sticks around in groundwater. Since it doesn’t degrade all that quickly, contamination can outlast the cleanup crews.

The Route to Safety in Handling Chemicals

From years in university labs and industrial sites, the lesson stands out: don’t treat chemicals like benign water bottles. Anyone working with dibromomethane ought to wear protective gloves, goggles, and always work with a functioning fume hood. More than once, I’ve seen colleagues downplay safety until a small spill brings sharp coughing and a hasty dash for fresh air.

Regulation and Accountability

Factories and storage facilities must keep close records and follow local laws about storing and transporting dibromomethane. Agencies require proper disposal, with strict limits on how much can end up in rivers or air. Regular audits help, but it only takes one oversight to turn a safe workplace into a hazardous mess. Neighbors and workers deserve transparency about what’s being stored and what steps are in place to prevent leaks.

Potential Steps for Safer Workplaces

Education stands as the first line of defense. No shortcut beats a solid list of do’s and don’ts, learned before anyone picks up a bottle marked with hazard symbols. Investment in leak detectors and air quality monitors pays dividends—these tools spot trouble before humans smell it. Companies can research alternative, less harmful chemicals for similar industrial uses.

Looking Forward

It’s tempting to treat specialized industrial chemicals as remote risks, locked away behind lab doors. My own run-ins with worrying exposures changed that outlook quickly. Good engineering, strict oversight, and a little humility about what we don’t yet know keep people safer—whether they wear white coats or work gloves. Dibromomethane carries risks worth respecting, not just reading about.

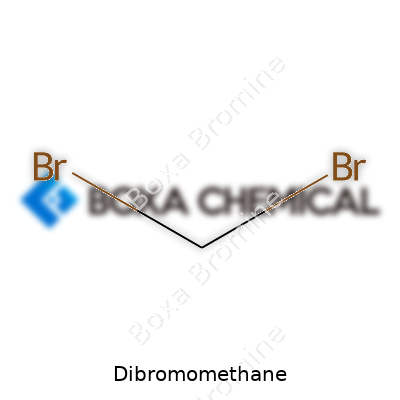

Understanding the Makeup

Dibromomethane, often found in chemistry labs and sometimes used in industry, carries the formula CH2Br2. Breaking this down, the molecule holds one carbon atom, two hydrogen atoms, and a couple of bromine atoms. Its name hints at the structure—"di" for two bromines, "methane" as a foundation with one carbon at the center.

Where Experience Meets Formula

Recalling my own lab days, I remember handling small vials labeled CH2Br2 with great care. Dibromomethane isn't something you come across at the grocery store. It's kept in tightly sealed containers, often away from sunlight. There’s a reason for that. The presence of bromine makes it heavier and denser than some other solvents and also a bit trickier to manage. Safety goggles and gloves weren't optional; splashing left you with irritation and regret.

Why Formula Details Matter

Sometimes, students ask why formulas become such a focus in science. In the case of dibromomethane, the chemical shape and composition answer all sorts of questions. Its two hydrogen atoms and two bulky bromine atoms mean it fits into different chemical reactions where one might want to swap the bromines out for something else. As a building block, CH2Br2 brings value to people working with organic synthesis or looking to make more complicated molecules.

The heavy bromine atoms give dibromomethane certain properties. It's denser than water, and it serves as a useful solvent for organic reactions. The world of synthetic chemistry sometimes feels crowded with possible choices, yet dibromomethane pops up because its chemistry is straightforward and predictable. The simple formula also means fewer surprises in reactions—a welcome thing in the lab.

Environmental and Safety Questions

Chemists talk about formulas like CH2Br2, but the questions don’t stop there. There's always a back-and-forth between usefulness and risk. Although dibromomethane helps in certain types of research, it doesn’t simply disappear after use. It can escape into air or water, and the bromine atoms don't go away easily. From time to time, environmental reports caution about its effect in the atmosphere. People handling it must stay alert to these risks.

Practical solutions start with storage. Keeping dibromomethane in airtight bottles keeps it from evaporating. Disposal requires special attention—pouring it down the drain simply isn’t responsible. Many universities and companies now track chemicals more closely and spend time training anyone who works with even small amounts. While some might see this as overkill, it helps prevent pollution and injuries.

Looking Forward

People often push for greener, safer chemistry. Replacing substances like dibromomethane isn’t simple, yet researchers chase new molecules that do the same job with fewer health or environmental tradeoffs. Finding alternatives means focusing on both performance and safety, not just swapping one formula for another. In teaching or practice, learning the reasons behind a chemical formula—like why CH2Br2 acts as it does—makes all the difference between rote memorization and real understanding.

Why the Fuss About Storage?

Dibromomethane shows up in labs and industries for a good reason—it's a useful chemical that plays a role in making other compounds and running reactions. It’s not a friend to your lungs, skin, or eyes, though. Spend enough time in a chemistry lab and you start to respect anything that can vaporize and cause headaches or worse. Containers left open or stored haphazardly have a habit of turning safe workspaces into health emergencies. There’s no room for shortcuts here.

Practical Steps That Matter

A sturdy glass container with a tight-fitting lid works far better than old plastic bottles that might crack. Polyethylene and polypropylene stand up to dibromomethane, so pick containers made from these materials. Direct sunlight turns this solvent into a bigger risk, breaking it down or damaging the bottle. Shelves in a cool, dry corner with good ventilation cut down on fumes and slow down decomposition.

Labels with clear, bold writing help everyone avoid mistakes. Countless times, people reach for a bottle and realize halfway into pouring that they grabbed the wrong one. Accidents go up when chemicals play hide and seek. Marking the container and checking it every few months changes the odds for the better.

Dealing With Spills and Exposure

Spills never come at a good moment. Dibromomethane soaks into skin and evaporates fast. A minor mess on a bench quickly becomes an air-quality problem. Keeping spill kits handy stops it from spreading. Absorbent pads or sand trap the liquid, letting you scoop it up without breathing in toxic fumes. Gloves and safety glasses shouldn’t gather dust—use them every time. Skin rash or breathing trouble catches up with you if you ignore that step.

Why Knowledge Isn’t Optional

People assume chemicals sold to businesses arrive with built-in safety. Yet, safety slips happen every day. Just last year, OSHA logged several accidents tied to improper storage of hazardous solvents, with expensive fines and harm to workers. Nobody wants to make the news for mistakes that a quick double-check could have stopped.

Training feels like a chore, but firsthand experience counts for more. Veterans in the lab guide newcomers, showing them not just how rules work, but why they exist. If everyone tries to cut corners, the risks multiply. Questions are free, but the cost of silence gets high.

Fixing the Bigger Picture

Checking local and national rules shapes how you store dibromomethane. Regulations set clear boundaries—strong ventilation, fire-resistant cabinets, limits on total quantity. Following them means more than dodging penalties. It protects your co-workers and keeps emergency responders safe if things go south.

Shoddy storage leads to expensive cleanup and possible harm to the environment. So, rotating stock and disposing of unused dibromomethane the right way keeps the footprint smaller. Companies that keep chemical safety high on their list avoid legal headaches and show care for their teams.

After seeing enough close calls in shared workspaces, it becomes clear—a strong storage routine isn’t just smart, it’s necessary. Shortcuts might save a few minutes, but never lead to a safe or productive workplace.

Understanding Appearance and Structure

Dibromomethane stands out in the lab, looking like a colorless crystalline liquid at room temperature. Pour it into a glass beaker and you notice it carries a distinct, sweet odor. Its structure isn’t tricky—just a carbon atom sporting two hydrogens and two bromines. Those heavy bromine atoms really shape how dibromomethane behaves, right down to how it pours and how fast it changes from liquid to vapor.

Density That Demands Attention

Pick up a flask filled with this stuff and it feels hefty for its volume. Dibromomethane clocks in with a density close to 2.5 grams per cubic centimeter. For context, water’s around 1 gram per cubic centimeter, making dibromomethane about two and a half times as heavy for the same space. Anyone cleaning up a spill quickly figures out it rolls and pools easily, running with gravity. That extra weight signals those bromine atoms packed at the heart of each molecule.

Boiling and Melting Points: What Lab Work Teaches

In the lab, boiling and melting points often separate safe work from dangerous surprises. Dibromomethane boils at roughly 97 degrees Celsius and melts just under -53 degrees Celsius. That means you don’t need much heat to start seeing vapor rise from an open bottle. It stays liquid over a wide temperature range, which helps if you’re storing it in most lab environments, but it also evaporates easier than you might expect on a warm day.

Solubility and Mixing in Practice

Here’s what comes up often: dibromomethane dissolves well in alcohols, ethers, and chloroform. Try mixing it with water and things go poorly—only a tiny bit manages to blend in. That non-polar nature leans on the bromine, shutting out water and making it stubbornly separate. This kind of behavior shapes how engineers and chemists use it, keeping it in the organic lane instead of expecting it to play nicely with cleaning runoffs or water-based solutions.

Vapor Pressure: Behavior in Storage and Safety

Folks storing dibromomethane need to keep its vapor pressure in mind, since it pushes into the air pretty easily at room temperature. Studies show a vapor pressure just under 55 millimeters of mercury at 25 degrees Celsius. For anyone working with it in a closed space, this number underscores how quickly it can fill the air. Good ventilation becomes less optional, especially since inhaling those vapors can irritate eyes and lungs. Poor handling leads to real risks.

Real-World Uses and Why This Matters

Dibromomethane finds its place in labs and industry—synthesis, solvent work, even contamination research. Yet every time you move it, its high density and tendency to produce vapor mean you need steady hands and solid safety practices. That distinctive sweetness in the air acts like a warning bell for leaks. Engineering controls like fume hoods and strong container seals help cut down exposure. Thinking about greener chemistry also motivates teams to swap dibromomethane for safer, less volatile alternatives where possible.

Learning From Handling Experiences

Anyone who’s clocked hours in a research lab remembers the lessons dibromomethane brings. Its physical properties reflect the power and challenge of working with halogenated organics. Respecting those heavy molecules, their fast evaporation, and low water solubility keeps scientists and technicians safer. Better container designs, regular air monitoring, and training sessions focused on liquid spills—all of these can shrink risks. Real lab know-how often comes from cleaning up a “just missed” spill before it turns into something memorable for the wrong reasons.