4,5-Dichloro-2-N-Octyl-3-Isothiazolone: A Deep Dive

Historical Development

People involved in industrial microbiology remember when mold and bacteria started to clog up cooling towers and paint buckets. As governments started caring about environmental protection, manufacturers looked for more effective and less toxic biocides. Out of this scramble came isothiazolone chemistry. Researchers noticed that adding alkyl groups changed how long the biocide stuck around, and chemists landed on N-octyl substitutions for longer-lasting power. The 1970s and 1980s saw big companies in Europe and America banking on these molecules, resulting in the introduction of 4,5-dichloro-2-N-octyl-3-isothiazolone, now a standard weapon in the fight against microbial spoilage. Through years of in-field feedback, and adaptation to regulatory shifts, this molecule went from an obscure chemistry to a global staple in antifouling and industrial protection.

Product Overview

4,5-Dichloro-2-N-octyl-3-isothiazolone, often known by trade names such as DCOIT or Sea-Nine 211, is a broad-spectrum biocidal agent. Its greatest strength lies in controlling slime-forming bacteria, fungi, and algae in harsh marine and industrial environments. Since marine coatings started relying on DCOIT, ships and aquaculture installations have seen reduced biofouling. That means fewer dry-dockings, lower fuel consumption, and longer asset service life. DCOIT's role now stretches far beyond the ocean—manufacturers use it in paints, polymers, cooling water systems, and leather goods. Its wide utility has roots in the balance between effective microbial control and comparatively low bioaccumulation.

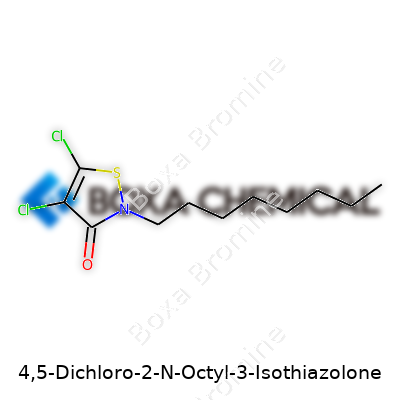

Physical & Chemical Properties

In practice, DCOIT arrives as a pale yellow liquid or a crystal depending on formulation, melting at approximately 75-77°C. If you’ve ever used it in a lab, you know its mild, somewhat medicinal odor and its solubility in solvents such as acetone or toluene. Unlike older biocides, it barely dissolves in water, which helps it stick around longer on submerged surfaces and slows leaching. Chemically, it's C11H17Cl2NOS—two chlorine atoms, a thiazolone ring, and an eight-carbon tail. This structure helps the molecule punch through cell membranes of microbes, disrupting enzyme function. It stays stable in storage if kept in cool, ventilated spaces, away from strong oxidizers or acids, but degrades quickly in alkaline environments or when exposed to sunlight over time.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Industrial packaging for DCOIT typically drums up in 25 to 200 liters, labeled with clear hazard warnings. Labels reflect its classification as an aquatic toxin, spelling out both physical and procedural hazards. In my experience, even seasoned handlers don’t take shortcuts—goggles, gloves, and chemical aprons are standard issue. Product spec sheets usually guarantee a minimum assay of 95% active ingredient, along with breakdowns for water, byproducts, and stabilizers. Regulatory regimes in North America and the EU dictate that environmental fate, toxicity, and safe handling routes all find space on the label, while Safety Data Sheets (SDS) give detailed advice for accidental exposure, fire hazards, and spill clean-up.

Preparation Method

Production of DCOIT relies on a stepwise route starting with 2-octyl-3-isothiazolone as a precursor. Manufacturers typically chlorinate the precursor using N-chlorosuccinimide or chlorine gas under controlled conditions. This step introduces chlorine atoms at the 4 and 5 positions of the thiazolone ring. The process takes careful monitoring—allowing the reaction to overrun risks unwanted side reactions. Purification happens by solvent extraction and recrystallization, with strict temperature controls and inert atmospheres. Yields often hover around 70-80% in industrial settings. Waste chlorinated organics and residual solvents require treatment before disposal, a process I've seen repeatedly scrutinized in environmental audits.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

DCOIT behaves as a moderately reactive electrophile, with the thiazolone ring and chlorine substituents driving its antimicrobial punch. In industrial settings, exposure to bases or intense UV causes degradation, breaking the molecule into smaller, less potent fragments. Scientists keep pushing the envelope by swapping the N-octyl tail for other alkyl chains, tweaking everything from toxicity to application lifespan. Formulators accompany the parent structure with stabilizers or encapsulating polymers to deliver slow, controlled release. Some recent patent literature has described co-polymers or microgranules incorporating DCOIT, offsetting leaching rates and improving adhesion to synthetic surfaces.

Synonyms & Product Names

Years of commercial spread mean DCOIT comes stamped with quite a few names. Chemical archives reference it as 4,5-dichloro-2-n-octyl-3(2H)-isothiazolone, 2-Octyl-4,5-dichloroisothiazolone, Sea-Nine 211, or CAS 64359-81-5. In regulatory documents, the acronyms run together, whether you read DCOL, DCOI, or just isothiazolone-O. On shipping manifests and inventory documents, I've seen it arrive as marine antifoulant or paint preservative, depending on the application sector.

Safety & Operational Standards

Anyone who’s worked long in maintenance or shipyard operations learns to respect the risks tied to DCOIT. Acute dermal and inhalation exposures produce strong irritant effects, necessitating full PPE and splash protection in bulk-handling setups. Eye protection is non-negotiable—one accidental splash can mean hours in the onsite medical bay. Safe operation relies on closed transfer systems, spill containment trays, and ventilation. Workplace standards from OSHA and the EU's REACH program limit airborne concentrations, and respirators stand ready if concentrations spike. Storage protocols require separation from strong acids and bases, with dedicated containment in temperature-controlled warehouses. Waste streams rich in DCOIT are never simply dumped—they demand neutralization and certified hazardous waste management.

Application Area

The biggest stage for DCOIT lies in marine antifouling coatings. Paint chemists chased durable solutions for submerged surfaces, and DCOIT delivered by draining the economic pain of dry-docking ships due to barnacle or algal fouling. Offshore oil platforms, fish cages, and floating docks lean heavily on this chemistry. Paint manufacturers have also turned to DCOIT for mildew-proofing interior coatings—especially in bathrooms, hospitals, and food processing plants. Industrial cooling water systems, paper mills, adhesives, and even plastics now draw upon its mold-blocking ability, while leather and textile producers turn to the molecule for preserving expensive raw materials against rot.

Research & Development

Development labs keep busy fine-tuning applications and studying interaction with a wide range of polymer carriers, surfactants, and co-biocides. Long-term field trials provide real data on release rates in salt and fresh water, and ongoing tweaks in the molecule structure adjust environmental break-down times. Innovation pushes toward microencapsulation, which extends surface protection while reducing run-off. Testing expanded into the impact on non-target aquatic species, pushing regulatory bodies to demand greener alternatives and more biodegradable delivery systems. Tight collaboration among industry, academia, and regulatory scientists frames the future of this chemistry—every new modification faces rigorous review for both performance and safety.

Toxicity Research

Toxicologists working with DCOIT have published plenty of data about its acute and chronic effects. The molecule quickly kills algae and invertebrates in laboratory bioassays at low concentrations, often under a few micrograms per liter, making it highly effective for target organisms but also a risk for sensitive aquatic life if released unchecked. Mammalian toxicity works out much lower, but workplace contact produces clear evidence of skin and eye irritation. In my experience translating MSDS sheets for warehouse teams, I’ve had to walk people through proper neutralization steps after accidental exposure. Long-term aquatic studies drive regulatory caps on permissible discharge in shipping and paint facilities, and the move towards alternatives reflects the pressure created by ecological footprint assessments.

Future Prospects

Environmental campaigners and ship-owners alike keep watching new developments in antifouling strategies. Pressure to produce biocides with fast breakdown and minimal non-target effects triggers waves of research across both legacy suppliers and startup chemists. Even so, DCOIT maintains a foothold in the market due to cost, track record, and consistent output. Paint makers are experimenting with hybrid coatings, blending traditional preservatives with enzymes or natural deterrents, cutting down the mass of active biocide. Regulatory frameworks may shift, but industry is slow to abandon molecules with known profiles and application histories. While green chemistry and non-toxic alternatives weigh heavier each year, incremental improvements in DCOIT’s environmental fate and delivery systems suggest its story isn’t finished yet.

Effective Mold and Fungi Control

Mold and mildew can cause problems inside homes, on outdoor decks, and in the walls of boats. 4,5-Dichloro-2-N-Octyl-3-Isothiazolone, which many people know as DCOIT, is a key tool used against these unwanted guests. DCOIT gets added to industrial paints and wood coatings to keep surfaces cleaner for longer. Instead of scrubbing away green stains year after year, people turn to coatings packed with this chemical. Years of experience as a homeowner taught me the headache of black mildew on fences and paint, especially in humid climates. Seeing how antifouling paints keep boats clear of algae and barnacles, it’s easy to understand why marine paints rely so heavily on DCOIT’s mold-fighting power.

Keeping Water Clean and Safe

In water treatment and industrial cooling towers, fouling from biological growth is much more than a cosmetic concern—it can clog pipes, ruin expensive machinery, and even cause safety hazards. DCOIT steps in as a consistent biocide. Factories and power plants add this chemical to water systems, which cuts back on bacterial and fungal buildup. Think of the pharmaceutical and paper industries, where water must stay free of living contaminants during production. Here, the alternative is frequent, costly cleanings and chemical overhauls. Instead, a controlled dose of DCOIT offers an ongoing barrier, protecting equipment and ensuring process reliability.

Preservative Power in Everyday Products

DCOIT doesn’t only safeguard boats and cooling towers. It turns up in consumer products, too. Leather shoes, textiles, sealants, and glues all tend to grow mold over time, especially in storage. Manufacturers mix DCOIT into these items during production. Its role is quiet, but the result is longer shelf life and less waste. Last year, I pulled out a pair of sandals that had sat in a dark closet for months; the faint chlorine-like smell told me some form of chemical protection was at work, saving my shoes from the trash. By slowing down the growth of mold, these treated goods cut down on spoiled stock and losses for both shops and buyers.

Questions About Risks and Regulation

Any substance that kills bacteria and fungi so effectively demands attention from regulators and scientists. The Environmental Protection Agency in the US and the European Chemicals Agency both keep a close watch on DCOIT. Recent studies show that high doses can harm aquatic life, which put stricter rules in place for how much companies should use and how waste gets treated. As a fisherman, I’ve watched once-clear waters fill with green scum near the marinas. Reports link runoff from treated boats and docks to these bursts of algae. Problems like this spark debate—how can we balance the need to protect buildings, boats, and products without causing bigger harm to the ecosystems around us?

Moving Toward Safer Solutions

Many companies in construction and shipyards look for safer options as pressure mounts over health and environmental safety. Some test natural oils and alternative antimicrobials, but cost and performance often lag behind what DCOIT delivers. Researchers continue to look for new formulas that can stop biological growth without the side effects seen with harsh chemicals. Community discussions, open labeling, and transparent regulations all help push the industry forward. Personal experience with garden shed mold removal showed me: people want solutions that work while feeling good about what washes down their drains. As more information comes out, builders and buyers alike start making choices that protect both homes and the world around them.

Understanding the Chemical

4,5-Dichloro-2-N-Octyl-3-Isothiazolone goes into a lot of paints, coatings, and preservatives because mold, algae, and bacteria don’t stand a chance against it. This chemical does what it promises: protects surfaces from the sort of nasty stuff that ruins materials. It’s useful, but being useful doesn’t make it risk-free.

Health Risks for Everyday Users

If you’ve ever worked with chemicals—maybe you stripped old paint from a boat hull or freshened up a pool liner—you know some of these substances do more than just get the job done. This isothiazolone, for instance, can irritate skin and eyes. Prolonged or repeated skin contact leads to redness, swelling, or worse. Inhalation can trigger trouble breathing, headaches, or dizziness if proper ventilation is missing. One 2021 occupational health study showed workers exposed without gloves or mask reported more skin rashes and allergic reactions than the protected group.

This chemical isn’t just some scary-looking formula either. Decades of research have linked chronic exposure to isothiazolones—not only this one—to increasing rates of contact dermatitis among painters, maintenance workers, and cleaning crews. Data collected by the American Contact Dermatitis Society points out these preservatives as top causes for job-related skin complaints.

Environmental Impact

Anyone painting a fence or treating a deck might figure the job ends at cleanup, but chemicals like this don’t vanish. Runoff from washing tools or rinsing containers creeps into local water. Once there, aquatic life faces trouble: research by the US EPA points to isothiazolones causing toxicity in small water organisms, and some fish species respond to even low concentrations with stunted growth or increased mortality.

Practical Steps for Safety

Back in my hardware store days, the best advice always started with gloves and goggles. Disposable nitrile gloves reduce the chance of skin contact. Proper-fitting goggles protect your eyes—no one likes chemical splashes, but the suffering is real if one lands in your eye. Ventilation changes the game inside: even a cheap exhaust fan or just a wide-open window helps keep fumes from building up. Home use doesn’t make these risks go away, just because the setting isn’t industrial. Labels should never get tossed aside; manufacturers aren’t just covering themselves, those warnings come from years of medical data and lab accidents.

For job sites and bigger projects, an industrial respirator does more than look official—it actually filters airborne particles. Anyone handling spills should keep cat litter or absorbent pads handy. Following up with a thorough soap-and-water scrub reduces lingering residue. I’ve seen colleagues get lazy after a long shift, figuring most of the chemical must be gone by then, only to develop itchy hands hours later. The chemical lingers longer than most expect.

Looking Ahead: Smarter Substitutions

Cutting down on risky chemicals often starts with asking—are there safer options? Ongoing research into green biocides might not provide drop-in replacements yet, but some companies have started shifting to less hazardous preservatives. Asking suppliers for full safety data sheets or demanding non-isothiazolone formulas pushes the market in the right direction.

If industry and DIY users stay alert to safety and keep nudging manufacturers toward better options, the need for harsh chemicals can shrink. Meanwhile, honest risk awareness and good work habits shield workers, families, and the local stream out back from unwanted surprises.

Pushing Back Against Mold and Bacteria

Mold loves to spread in dark, damp corners. Bacteria don’t need much encouragement either. A lot of businesses—especially those working with water, wood, or coatings—go looking for agents that keep these invaders at bay. That’s where 4,5-Dichloro-2-N-Octyl-3-Isothiazolone finds a regular crowd of users. People in the paint and coatings world bank on it for mildew resistance. I’ve talked to manufacturers who see entire batches of product spoiled because of one missed step in the fight against microbes. They count on certain chemicals for real-world results, not just lab tests.

Protecting Wood and Construction Materials

If you walk through a lumber yard long enough, you’ll hear stories about rot and surface decay ruining stacks of timber. Construction and wood preservation crews use this specific compound as part of their treatment mix. The chemical helps extend the life of outdoor structures—think decks, fences, and docks that would otherwise fall apart after a few seasons of sun and rain. Some folks tend to overlook the savings that come from keeping that material solid year after year, but wood producers and contractors certainly don’t. The headaches from customer callbacks and warranty issues drop when they use additives that get the job done.

Safeguarding Industrial Processes

Paper mills, cooling towers, and industrial water systems don’t look all that similar on the surface, but they share a common pain point: slime-forming microorganisms. Once biofilms start to develop in a water system, efficiency takes a nosedive. Pumps clog up, filters gum shut, and everything from power bills to repair costs starts creeping up. By dosing water systems and process fluids with strong biocides like 4,5-Dichloro-2-N-Octyl-3-Isothiazolone, plant operators keep the operation moving. That’s not just about keeping the books green for a quarter—it can keep whole factories from grinding to a halt.

Challenges and the Way Forward

No one gets a free ride here. Used carelessly, this chemical—like most strong biocides—can raise questions about environmental and health impacts. I’ve seen folks in manufacturing take extra training so they understand exactly how to handle and dispose of treatments. Regulatory hurdles continue to pop up, as agencies look to balance public health and industrial needs. The shifting ground means manufacturers need to be smart about not just the concentration, but also what happens after the product goes out into the world. Some are investing in improved monitoring and developing safer formulations with lower exposure risks.

Real Stakes, Real Solutions

Most people outside these industries never think twice about what keeps their painted walls looking fresh, or their deck solid through sixteen winters. There’s a lot riding on the choice of antimicrobials behind the scenes. Technical know-how, local laws, and changing weather patterns all influence how companies approach this challenge. The conversation isn’t just about today’s mold or bacteria—it’s about how these industries adapt over time, keeping products strong while watching out for workers, customers, and the planet. Product longevity, lower costs, and cleaner systems matter today just as much as they did fifty years back, even if the solutions keep changing.

Understanding Its Place in Modern Industry

4,5-Dichloro-2-N-Octyl-3-Isothiazolone (DCOIT) came into focus through its widespread use in paints, coatings, and marine antifouling agents. People working in shipyards and construction have recognized its strong biocidal properties for keeping algae and barnacles at bay. As an antimicrobial, it helps extend the life of materials exposed to water. My own time spent along the docks revealed how often these compounds get slapped on surfaces without much thought about where they end up.

Migration and Persistence in Aquatic Systems

Runoff never stays put. Rain splashes DCOIT from treated boats and docks into nearby streams, lakes, and estuaries. Even small spills during paint mixing add up over years. While rapid breakdown in laboratory conditions sometimes gives the illusion of safety, the real world tells a different story. Sunlight, temperature, and the soup of other chemicals in local waters change how fast DCOIT degrades. In slow-moving rivers or deep harbors, residues linger longer. Personal observations of algae die-offs in places near busy marinas raise flags, especially since DCOIT can stay toxic well after application.

Effects on Non-Target Organisms

Wildlife experts and fishermen have worried about strange changes in local populations. DCOIT doesn’t discriminate: plankton, small crustaceans, and fish eggs sit on its hit list along with barnacles. Research shows that even at low parts-per-billion, DCOIT disrupts cell membranes in tiny aquatic animals. These are the foundational species for the food web. A single exposure event in spring when fish spawn can wipe out an entire year’s recruitment.

During a local river work project, a few angling groups noticed fewer minnows and shrimp. Lab results later tied mortalities to a nearby antifouling paint operation. These stories ricochet through small communities that depend on fresh water and fish for food and income. I’ve worked alongside locals who pointed out how catching fewer baitfish changes the economics of their livelihoods.

The Roadblocks of Regulation and Testing

Testing protocols often lag behind industrial chemistry. While government agencies urge risk assessments, many focus on acute toxicity, not on low-level chronic exposure or buildup in sediments. DCOIT breaks down in sunlight but tends to bind tightly to mud, where worms and clams feed. The chemical then cycles through predators like ducks and fish. People harvesting wild shellfish in estuaries face risks that rarely show up in regulatory reports.

In my experience, few users receive clear guidance on proper application or safe disposal. City recycling centers and hazardous waste pickup days don’t always accept unused marine paints, leaving contractors to stash leftovers or rinse brushes into drains.

Paths Toward Lower Impact

Labels need to include plain language about risks to wildlife, not just warnings for humans. Better education for contractors, boat owners, and paint retailers would help: stuff left to dry on a tarp can keep toxins out of waterways. Advances in non-toxic fouling deterrents—from silicone coatings to ultrasonic systems—offer hope for shifting away from broad-spectrum chemicals. Many European harbors now restrict DCOIT, door-by-door, from high-traffic marinas, nudging demand for safer alternatives.

A well-informed public, strong monitoring of aquatic life, and steady support for chemical transparency can make a huge difference. The environmental footprint of DCOIT doesn’t just lie in its formula but in how communities choose, handle, and regulate it.

Understanding the Risks in Everyday Terms

Handling chemicals like 4,5-Dichloro-2-N-Octyl-3-Isothiazolone (DCOIT) doesn’t just fall to the scientists and engineers. Folks in maintenance, warehouse management, or anyone touching water treatment or coatings get close to this substance. Small mistakes or short-cuts can create big problems for health and the environment, so nobody can afford a casual attitude.

Storing DCOIT with People and Safety in Mind

Storage should aim to protect both people and the material. DCOIT brings respiratory, skin, and eye hazards, and a low flash point. Those facts underline that a basic shelf in a crowded tool room isn’t good enough. I’ve seen warehouses where small leaks went unnoticed for weeks, stinking up the place and forcing costly shutdowns to fix a “minor” spill.

It helps to use a dedicated chemical cabinet, away from food or other supplies. Solid labeling goes beyond legal compliance; clearly marked shelves stop confusion during a busy shift. Temperature swings push up the volatility and might turn manageable vapors into a health threat. Keep the container out of sunlight, away from heat sources, and sealed. Double-checking gaskets and caps saves money and headaches. I’ve watched bottles degrade over time—plastic breaking down, seals cracking—which turned routine storage into a hazard overnight. Avoiding incompatible substances matters too, since oxidizers nearby mean possible reactions nobody wants to clean up.

Personal Responsibility in Disposal

DCOIT disposal trips up plenty of workplaces. It doesn’t just dissolve safely down the regular drain—the isothiazolone structure can poison water sources. Pouring leftovers into the trash flies against local rules and puts waste handlers at risk. In my experience, employees often don’t know the right method and hope a container left on the bench will “sort itself out.” It never does.

Instead, work with licensed hazardous waste handlers. Local environmental agencies have lists of reputable services and can guide companies that don’t have an in-house safety officer. If you manage a site, invest the time talking to these experts instead of letting confusion build. Keeping detailed logs for every use, from receipt through the last residue, fits best practices and keeps surprises away during safety inspections.

Reducing Future Risks

Training changes how people treat DCOIT. In safety meetings, showing how personal protective equipment—gloves, goggles, long sleeves—makes a difference hits home much more than printed warnings. Regular refreshers remind staff that just because a chemical sits quietly on a shelf for months doesn’t mean it’s safe to ignore. I’ve watched attitudes shift when people see a demonstration of how a small spill can spread or how fast fumes get out of hand in a closed space.

No process runs perfectly, so spill kits should remain stocked and easy to access, not buried under other supplies. Prompt cleanup protects both co-workers and the surrounding community. Encouraging a culture where reporting mistakes doesn’t get someone in trouble leads to faster resolutions. As I’ve learned, open communication matters as much as any technical fix.

Building a Safer Chemical Culture

Every step, from storage to disposal, makes up a chain. Weakening one link puts real people in harm’s way and invites regulatory trouble. By sticking to clear routines, doubling down on training, and building partnerships with waste experts, teams avoid common mistakes. Keeping DCOIT out of landfills and waterways takes patience and vigilance, but I’ve seen workplaces pull it off with some planning and respect for the risks.