2-N-Octyl-4-Isothiazolin-3-One: An In-Depth Look

Historical Development

Chemistry has always chased after compounds that keep products fresh, clean, and free from microbes, and 2-N-Octyl-4-Isothiazolin-3-One (OIT) has taken a winding road to reach this point. Decades ago, industries started to notice that simple preservatives didn’t quite cut it—molds and bacteria would adapt, and old biocides faded under sunlight or dissolved too quickly in water. Scientists began scouring the isothiazolinone family, seeking molecules with stronger backbone and broader spectrum. OIT stood out: discovered during the biocide boom of the late 20th century, it survived early field trials in paints, wood, and water treatment systems, where other chemicals flopped or left behind toxins no one wanted near their homes or waterways. Its path has sparkled with patents, regulatory scrutiny, and steady tweaks to stay ahead of growing microbial resistance.

Product Overview

OIT’s reputation as a robust, long-lasting biocide rests on how stubbornly it resists breakdown. This pale yellowish liquid, often called “octylisothiazolinone” or just “octyl Kathon,” finds its way into coatings, sealants, and industrial fluids precisely because bacteria, algae, and mold can’t handle its bite. Walking down the paint aisle, picking up a can for outdoor furniture, or reading the label of a deck stain, OIT lurks among the fine print. Big names in chemical manufacturing ship it in drums, often marked with warning labels and concentration ranges to match intended industrial applications. This isn’t an additive for groceries—OIT works by disrupting enzymes that bugs need, so it’s used where human skin or food contact won’t happen.

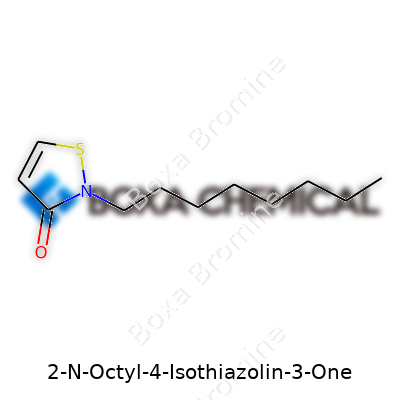

Physical & Chemical Properties

OIT boils at around 320°C, a feat for an organic molecule. Its melting point hovers near -45°C, letting it flow even on cold factory floors. In water, its low solubility keeps it around longer in treated products but limits use in anything that demands a clear solution. This oil-friendly character encourages paint manufacturers to blend it with other hydrophobic ingredients, while offering stability across a range of pH and temperatures. Its slight acrid odor gives away its chemical kinship with other isothiazolinones. Chemically, OIT binds a nitrogen, sulfur, and oxygen together in a five-membered ring, with a long tail of eight carbons that sets it apart from short-chain cousins like methylisothiazolinone—a difference that matters for both effectiveness and safety.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Technical data sheets show OIT usually supplied in concentrations from 45% up to 99% for blending flexibility. These specs list refractive index, viscosity, flash point above 100°C, and pH stability across 3.5-9.5. Any container must clearly list CAS number 26530-20-1 for compliance, along with hazard pictograms tied to skin irritation and aquatic toxicity. Labels carry a batch number for traceability—a crucial detail for recalls or regulatory checks. Transport documentation never skips hazard codes, and manufacturers must register OIT under relevant chemical control regulations across different countries. Users in the field rely on this information, since errors in labeling or mixing concentration invite regulatory headaches or worse: product recalls that stick in public memory and hurt trust for years.

Preparation Method

Synthesizing OIT starts by reacting octylamine with carbon disulfide, generating an intermediate thioamide. This compound then undergoes cyclization with chlorine and sodium hydroxide, yielding the isothiazolinone core with a side tail tailored for the right balance between oil solubility and antimicrobial strength. Downtime in the reactor, careful temperature control, and filtration step right after reaction all decide the final purity. Plant operators often run side-reactions to check for byproducts—since residual reactants or breakdown products either ruin the product or kick up waste treatment costs. Modern methods skip heavy metals, focusing on greener oxidizers and recyclable solvents to keep environmental footprints lower.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

OIT’s backbone supports some chemical tweaks. Adding a functional group on the octyl chain or altering the ring positions changes how it binds to bacteria or resists sunlight. Research labs test blends with other preservatives—OIT plays well with zinc, copper, and some phenolics, which can jointly widen its kill spectrum or slow down resistance. Industry insiders know that reformulation for regulatory shifts means balancing efficacy against new toxicological flags. For those prepping custom blends, OIT must avoid strong acids or bases and withstand the mild heat of product storage; otherwise, degradation kicks in, setting off color change or even forming allergens not listed on the original specification sheet.

Synonyms & Product Names

People outside chemistry circles know OIT by a gallery of names: 2-Octyl-4-isothiazolin-3-one, octylisothiazolinone, octyl Kathon, sometimes as “OIT-based preservative.” Trade names—often shielded by branding regulations—include Skane M-8, Bioban OIT, or Preventol OIT. Paint professionals, wood preservers, and water-treaters might check SDS sheets and spot these words. Every synonym traces back to the same molecule, giving users a way to cross-check what’s actually going into their products when ingredients lists stretch long.

Safety & Operational Standards

Handling OIT draws concern over direct contact and environmental hazards. OSHA guidelines demand gloves and splash-proof masks in plants. The chemical has a reputation for causing skin sensitization and, with concentrated exposure, significant eye irritation or redness. Spills in the workplace get neutralized with absorbent materials and shuttled to approved waste disposal—not down the drain. Across the globe, regulatory bodies such as the EPA and EU’s ECHA set hard limits on OIT concentrations in consumer products, especially given its toxic effect on aquatic life. Safety data sheets highlight the need for ventilation, shower stations, and prompt decontamination for accidental splashes. Risk assessments for storage demand locked, labeled containers away from oxidizers or acids. This matters at every level—factories get shutdown orders during safety audits if these rules get skirted.

Application Area

The construction industry adopted OIT in outdoor paints, caulks, and sealants for its resistance to algae and clear mold lines on treated wood. It carves out a place in metalworking fluids, where its low volatility and thermal stability match machine shop needs. Leather goods, adhesives, and concrete additives also benefit: OIT keeps out black stains and green mosses that drive product returns. Paper mills use it to push downtime between system cleanings, avoiding microbial fouling that shreds equipment or leaves musty odors on final products. Yet its use in personal care gets tightly policed; research exposed allergy risks and skin irritation at concentrations used in early shampoos, leading to bans or lower limits. OIT’s niche lies in places where its robust preservation trumps mildness needed for direct skin contact.

Research & Development

R&D around OIT never stands still. Companies and universities examine how its molecular structure interacts with fungal cell walls and bacterial membranes, testing mutants for reduced resistance. Computational chemists build QSAR models, mapping how tweaks to the octyl chain shift effectiveness against new families of mold. Startups join the race by searching for greener synthesis routes—cutting down solvent waste and cutting energy costs—while multinational corporations push for blends that cut total chemical load but keep microbes at bay. Beyond killing power, researchers dig into OIT’s environmental breakdown: some studies reveal that sun, time, and soil microbes chop up OIT, but not always fast enough. These findings feed into revisions on use guidelines, disposal, and agricultural runoff regulations.

Toxicity Research

Toxicologists have traced OIT’s exposure risks across cells, animals, and field workers handling big shipments. Studies show skin absorption can trigger rashes or worse in those with allergies. Fish and small stream invertebrates fare even worse, with OIT’s breakdown products blamed for population drops near industrial outflows before water treatment plant upgrades. Chronic exposure in mammals brings mixed results: only high concentrations—far more than detected in end-use paints or paper—spark off organ effects, but low-level, long-term data stacks up slow. Agencies like the EPA and EU commission independent trials, setting ‘no observed effect’ levels that trend downwards when new research appears. Practically, these results mean workplaces invest more in closed system handling, while regulators force industries to cut back or monitor runoff.

Future Prospects

OIT’s future doesn’t look simple. On one side, growing calls for longer-lasting, effective preservatives in building materials, industrial fluids, and manufacturing keep the demand strong. On the other side, environmental and toxicity concerns, especially the impact on water life, drive research for safer alternatives and tighter limits on use. High-performance coatings, bio-based construction materials, and low-impact manufacturing all place pressure on OIT’s makers to innovate—either by reformulating compounds, lowering used concentrations, or developing encapsulated forms that release only when needed. Regulatory landscapes shift year by year. Firms investing in better traceability, more eco-friendly synthesis, and transparent safety data stand a better chance of keeping OIT in their product lines, at least where no other preservative works as well in tough, algae-prone environments. Whether in building sites, factory lines, or R&D labs, OIT’s story looks far from finished.

Where You’ll Find It Working

2-N-Octyl-4-Isothiazolin-3-One, often shortened to OIT, shows up in places where mold, mildew, and bacteria cause real headaches. Most people will never see its chemical name printed on a label, but OIT makes life a little easier behind the scenes. You might notice fewer musty smells in freshly painted rooms, or see less gunk build up in your outdoor deck stain, and give the credit to some serious chemistry.

OIT belongs to the isothiazolinone family—a group of preservatives doing the heavy lifting in paints, wood coatings, and even household cleaners. It keeps these products from turning sour, both figuratively and literally. Paint sitting in a warehouse through a steamy summer has a shot at lasting long enough for someone to actually use it. Wood on a fishing dock can handle relentless rain without sporting a coat of furry mold. Beyond paint and stain, OIT turns up in adhesives, industrial coolants, and even certain leather treatments. Its reputation rests on blocking the kind of microbial growth that can cost companies a lot of money and eat away at the look and strength of a finished product.

Why the Industry Cares

Factories and workshops everywhere rely on materials that last. Years back, I worked on renovations where moldy paint and fuzzy stains left everyone with tough choices—scrape and start over, or just hope for the best. More often than not, the problem stemmed from water and heat inviting mold right into brand new projects. Preservatives like OIT create a real line of defense, reducing waste and keeping jobs on schedule. In bigger settings such as paper mills or cooling towers, unchecked bacteria can turn a system into a breeding ground. OIT stunts that growth at the root.

It also means fewer surprise recalls. Nobody wants a shed full of spoiled paint or outdoor decking that grows slippery overnight. Companies aim for long shelf life and customer trust, and OIT helps them get there. For people with allergies or asthma, controlling mold and bacterial contamination keeps indoor air safer. There’s value here beyond profit: fewer ruined products mean fewer things heading to the landfill, tying into more responsible resource use.

What About Safety?

OIT’s power as a biocide brings up questions about health and environmental impact. The European Chemicals Agency and the US EPA have both kept this compound on their radar for years, sifting through data on its risks and benefits. Researchers flagged local skin irritation and aquatic toxicity as real issues, especially in settings where it’s washed directly into rivers or lakes.

I’ve handled paints and coatings most of my working life, and I don’t take shortcuts with gloves or masking up, especially after learning OIT can cause rashes with repeated contact. Anyone using it should read the safety sheets and not treat it like a harmless ingredient. Regulators have set limits on allowed concentrations and put pressure on manufacturers to label and explain usage clearly.

Finding Balance: Using OIT Responsibly

Balancing the benefits with the risks keeps manufacturers on their toes. There’s a push in the industry to use exact doses—enough to keep things fresh, but not more than needed. Scientists study breakdown rates and how quickly OIT leaves the environment. New product research explores safer blends or alternatives, but so far, nothing matches OIT’s sturdy protection in tricky spots like outdoor stains and high-moisture paints.

Until there’s something better, smart use goes a long way. Workers stick to protective gear, disposal systems cut runoff, and honest communication helps builders and homeowners know what they’re working with. Every step counts toward making tough jobs safer and cleaner, from the first brushstroke to the final rinse.

What is This Stuff and Why Should We Care?

2-N-Octyl-4-Isothiazolin-3-One, often just called OIT, slips into daily life more quietly than most chemical preservatives. Paint, wood coatings, adhesives, and personal care items use OIT to keep mold and bacteria away. Companies like adding OIT to help make their products last. Standing in a freshly painted room or using household sealants, you’re likely breathing in cleaner air because of OIT. But does using OIT trade off safety for the sake of longevity?

Human Health Risks

Worry about chemicals comes from people actually getting rashes, headaches, or eye irritation. The science is clear—OIT can cause skin allergies. Some folks who handle OIT in factories or construction wear gloves for a reason. Numbers from the European Chemicals Agency show OIT as a skin sensitizer, flagging it for potential reactions even at low doses. The irritation isn’t rare; OIT shares a reputation with MIT and CMIT, cousins in the isothiazolinone family, for triggering allergic contact dermatitis. Think workers in carpentry or people dealing with paints and glues. With home exposure, young kids get especially vulnerable because their skin is thin, and they love to touch everything.

Can OIT Build Up in the Body?

OIT doesn’t stack up in organs like mercury or PFAS, but repeated skin contact keeps the risk going. No one really eats OIT, but research by government health agencies runs tests on how chemicals like this pass through skin. The real trouble might not show up right away; one splash may be irritation or nothing at all, while repeated use could teach the immune system to overreact. Industry can switch to non-sensitizing biocides, but many stick with OIT because it works well and is cheap.

Environmental Impact: The Water Worry

Washing paintbrushes or rinsing a sealed floor off can move OIT from homes into nearby streams and rivers. Water treatment plants catch lots of contaminants but struggle with low-dose persistent chemicals. Studies in Europe tracked OIT in rivers near big cities and manufacturing hubs. OIT is toxic to fish and aquatic insects at low levels. Even at concentrations found in polluted streams, it can stop fish eggs from hatching or stunt growth in tadpoles. There’s a ripple effect: disrupt tiny life, and birds or bigger fish higher up in the food chain lose meals.

What Would a Safer Path Look Like?

I read labels more than ever, hoping for words like “biodegradable” or “low toxicity.” Often, those words don’t match up to the fine print where OIT lurks. Public pressure and new rules in Europe and California push companies to explore safer options. Manufacturers have started swapping in less allergenic preservatives in consumer products—often after lawsuits or a flood of allergy complaints. For paints and building materials, shifting toward borates or silver-based agents tends to cost more up front but helps dodge some health problems.

The balance swings between product quality, human health, and environmental protection. Paying a bit more for safer construction and home products feels worth it when nails or allergic reactions are off the list. Small steps—washing brushes properly, using personal protective gear, and supporting tougher chemical regulations—add up. Chemicals like OIT make life easier on one side but ask for attention from everyone along the chain, from workers to families to wildlife downstream.

Understanding the Material

2-N-Octyl-4-Isothiazolin-3-One may sound technical, but folks in coatings, water treatment, and personal care recognize it as a serious biocide. It keeps mold, fungus, and bacteria away from paints and industrial fluids. Experience and safety records highlight that this material works well for jobs no other ingredient can handle, yet it brings risks to personal health and the environment if ignored. Getting careless with it opens the door to skin issues, breathing problems, and trouble for any aquatic system it touches.

Safe Storage Is About Strategic Choices

Storing this chemical isn’t just throwing a drum on a shelf. Moisture in the air ruins its properties and even small spills on porous surfaces can linger. So, it goes in a cool, dry area with steady ventilation. Sunlight and heat speed up its breakdown and raise the odds of pressure build-up or container bulging. Direct sunlight or high temperatures don’t just threaten quality, but also safety.

Metal containers show too much reactivity with isothiazolinones. Polyethylene or high-quality plastic holds up best. Chemists often remind colleagues that even a stray drop can put a stain on an entire batch, so sealed lids remain the rule. Safety data, filed with most chemical suppliers, spells out shelf life—usually under a year in tight, original packaging. Anyone cutting corners to save space or time risks chemical changes or leaks.

Keeping People and the Environment Safe

Routine handling loads more responsibility onto the team. Gloves aren’t just a formality—nitrile keeps contact at zero, and eye protection isn’t optional. Fumes from this biocide hit quicker than some folks realize, especially if ventilation slips or a spill goes unnoticed. I’ve seen redness and rashes pop up with bare-skin mistakes, and plenty of companies invest in safety showers and spill kits nearby these storage zones for this very reason.

Respirators move from optional to required when a project calls for open vats or mixing. Emergency instructions matter, too. Doors marked with clear signage and quick routes to first-aid limit panic if spills or splashes occur. I’ve talked with operators who wished these measures were in place before their first unlucky exposure.

Spill and Waste Wisdom

Any drop landing somewhere it shouldn’t finds a way into drains or soil. It doesn’t break down easily and messes up water life in tiny amounts—a single mishandling spreads real harm. Industrial managers rely on absorbent pads and never use sawdust, which reacts poorly. Waste collected this way heads straight for licensed disposal; pouring it out backs up into rivers or groundwater, risking fines and cleanup headaches.

Some plants run water monitoring next to their storage areas, catching leaks before they cause damage. Simple recordkeeping—date received, date opened, storage location—gives quality managers quick answers about chemical performance and accident tracing. Making these processes routine keeps insurance claims lower and trust higher.

Responsible Culture

Every chemical with hazard symbols demands respect, but this biocide pushes the point home. Training new hires on product-specific dangers, holding regular drills, and checking equipment keeps accidents rare. Fostering a no-shortcut culture rewards everyone from the warehouse to the lab.

Companies open about their protocols see fewer injuries. Inspectors and community watchdogs look closely at high-hazard substances, especially those linked to aquatic toxicity. With 2-N-Octyl-4-Isothiazolin-3-One, everyone from storage managers to process engineers benefits from attention to detail, open communication, and a steady commitment to doing it right every time.

Tough Problems, Demanding Solutions

From moldy walls in old classrooms to algae-covered fountains on hot days, microbes show up everywhere life and water meet. Keeping mold, mildew, and bacteria in check protects property, health, and peace of mind. Many manufacturers turn to 2-N-Octyl-4-Isothiazolin-3-One, known as OIT, to answer the call. Its use runs from paint cans at the hardware store to household cleaners at the supermarket. My years scraping out musty corners in family basements taught me just how relentless mold can be, and how much difference the right chemical can make.

How OIT Battles Microbes

OIT breaks down cell walls and interferes with essential enzymes. Fungi and bacteria have little chance when directly exposed. In real life, I’ve seen paints mixed with OIT hold up for years in bathrooms that otherwise might grow black streaks over the shower and sink. Studies back this observation: research from coating technology journals shows OIT keeps mold counts low in treated surfaces, even under damp conditions.

It’s been picked for its broad action, especially where other chemicals like methylisothiazolinone spark allergies or regulatory scrutiny. OIT offers strong performance at low concentrations, which matters for costs and environmental spillover. Workers in building renovation swear by products preserved with OIT because they deal with fewer callbacks for mold remediation.

The Downside: Health and Environment

No biocide comes without baggage. Studies report that direct skin contact with high OIT levels can irritate or cause allergic reactions, especially in sensitive people. This isn’t just a minor concern: European regulators keep a close eye on OIT’s use in personal care products or anything likely to touch bare skin. As a parent and someone who has family members with allergies, I keep an eye on product labels and prefer items designed for minimal exposure. In the environment, OIT breaks down faster than some older biocides. Still, aquatic organisms can suffer from even moderate concentrations, a real issue for city wastewater systems already worried about chemical load. The fishing community, which my cousin relies on for a living, sees the consequences of pollutants that build up in rivers and streams.

Finding a Balance: Responsible Use

For industries and trades, OIT remains a valuable weapon in the fight against mold and bacteria. What works for hospitals might be overkill or a hazard in kitchens; this needs real attention, not a one-size-fits-all answer. Tighter regulations on labeling and maximum amounts in consumer products help cut down on unnecessary exposure. Manufacturers could push for encapsulation technology—tiny capsules that only release OIT when mold or bacteria gets close. This has shown promise in newer paints and coatings, giving microbes a nasty shock without flooding the air or water with chemicals.

The quest for trusted and safe antifungal and antibacterial agents will never end. OIT holds a place because it reliably discourages unwanted growth, saves time, and prevents damage. Yet it asks for vigilance. Those using it, or buying products containing it, benefit from honest information, proper handling, and an eye on science as safer alternatives and new techniques emerge.

Everyday Risks Linked to 2-N-Octyl-4-Isothiazolin-3-One

2-N-Octyl-4-Isothiazolin-3-One, or OIT, keeps bacteria and fungi from taking over paints, adhesives, and industrial fluids. The trouble is, this chemical, while useful for businesses, brings health hazards too easily dismissed outside factory walls. My experience in construction showed me that skin contact happens even with the best gloves. Tiny exposures stack up fast, especially if nobody talks about why it doesn’t wash off as easily as paint.

The Skin Tells the Story

OIT gets under your skin. People sensitive to chemicals break out in rashes, blisters, and persistent itching. The European Chemicals Agency classified it as a skin sensitizer for good reason. One time, I saw a painter developing red streaks on his forearms after repeated use of water-based wood stains loaded with OIT. He shrugged it off as an irritation from his shirt, but the allergy never left him. This chemical rewires the immune system’s response.

Breathing in the Problem

It’s not just touch. OIT finds ways into the air when mixed or sprayed, and folks working with paints or industrial-cleaning fluids can inhale droplets. Studies have shown OIT can irritate noses, throats, and lungs. My nose always tingled when I checked labels and found this chemical present, especially when mixing latex paints in a non-ventilated shop. Prolonged exposure led to coughing fits and lasting sinus pressure for some of the crew.

Hazards That Stick Around

Environmental risks line up behind the health concerns. OIT doesn’t vanish after the job’s done—runoff from cleaning brushes, spills, or washed-down floors sends it into drains. Aquatic animals pay the price. Research from aquatic toxicity tests showed OIT hurts fish and aquatic invertebrates at concentrations lower than you might expect. In practice, a crew once washed tools near a storm drain, and dead bugs and tadpoles floated up the next day. It made the whole team pause before rinsing anything out again.

How We Can Do Better

Staying safe means more than reading the warnings. Product education needs an upgrade, especially for small contractors and maintenance staff who receive less formal training than big manufacturers. Businesses can swap OIT-laden products for alternatives with shorter environmental half-lives or lower toxicity, though those tend to cost more. On my last job, the client agreed to pay a bit extra for paints certified skin-friendly. Everybody’s health benefits, and nobody lost sleep over runoff contaminating local streams.

Strict ventilation and reliable personal protective equipment stop much of the harm. Impermeable gloves and face masks work, but folks ignore them or reuse disposable gear to cut costs, often leading to trouble. Regular safety briefings help build new habits. Labeling changes would help too—plain language warnings about skin and inhalation risks stick with people more than unfamiliar hazard symbols.

Managing OIT means caring for more than production numbers. This chemical saves products from spoilage; it shouldn’t spoil the health of people handling it or the natural world we share.