1,2-Benzisothiazolin-3-One: A Close Look

Historical Development

Since the early 20th century, researchers have toyed with the molecular backbone of benzisothiazolone. Back then, the promise of heterocyclic chemistry included antimicrobial agents, and 1,2-Benzisothiazolin-3-One stood out. Early patent filings in Europe during the 1960s demonstrate industry interest growing right alongside the recognition for water-based industrial processes. As waterborne coatings and preservatives took over from solvent-based formulas in the 1970s and 80s, industries leaned more on this compact, effective molecule for its broad-spectrum activity. What’s especially striking is the resilience of its popularity: decades later, manufacturers still count on it while tweaking the surrounding cocktail of ingredients to meet newer standards.

Product Overview

1,2-Benzisothiazolin-3-One—often known simply as BIT—finds itself on lab benches and factory floors wherever folks need to halt mold and bacterial growth. The material comes as a slightly yellowish, powdery solid or dissolved in preservative concentrates, ready for blending into paints, adhesives, detergents, and even inks. Multiple suppliers list it under a slew of trade names, each tweaking the concentration or formulation a bit to suit a different use-case. One thing stays constant: if a material sits in a bucket of water for weeks, BIT bumps up the shelf life.

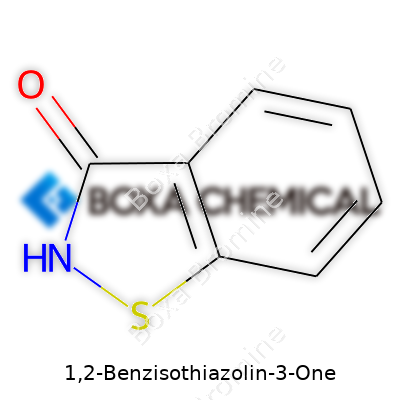

Physical & Chemical Properties

The chemical formula gives BIT a weight near 151 grams per mole. It melts in the 155-158°C range, giving it stability well above most room and plant temperatures. BIT dissolves only sparingly in water but blends better in polar organic solvents. This solubility profile matters—a lot—because the molecule needs to disperse to work as a preservative. Not much about the structure has changed since BIT’s original synthesis: the sulfur-nitrogen ring makes it tough on microorganisms but stable enough for storage. The molecule resists breakdown in the dark but can degrade under direct light or very high pH.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Professional and regulatory labels list BIT concentrations, sometimes down to the ppm level, especially when destined for water-based paint or personal care bases. Because of global rules, technical datasheets spell out purity levels (often upwards of 98%), any diluents or stabilizers, and hazard statements. The European Union, the United States EPA, and China’s GB standards keep a watchful eye on BIT in finished consumer goods, which pushes producers to keep meticulous batch records and run routine purity tests. Each batch passes through quality checkpoints for pH, melting range, color, and moisture before heading out the door.

Preparation Method

The original synthesis starts from o-aminothiophenol and chloroacetic acid, condensing them under mild to moderate heating. This method gives a ring closure that locks in the sulfur and nitrogen, giving the signature structure. To scale up for industry, operators batch the two starting materials into jacketed vessels, keep the heating slow, and avoid water splash that would throw off consistency. Newer approaches might tweak the solvent or use safer intermediates, but the backbone of the process hasn’t changed much—it’s still a practical, direct route to an efficient preservative.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

BIT’s reactive sites let chemists alter it for tailored applications. Halogenation, substitution on the aromatic ring, or even different acylations shift antimicrobial activity without changing the core ring. Manufacturers often mix BIT with other isothiazolinones to stretch the spectrum or tweak the solubility for tricky emulsions. Some scientists work on grafting BIT residues onto polymers to lock antimicrobial properties right into plastics—especially handy for medical tubing or storage tanks. These derivatives might cost more, but they carve out niches where old-fashioned preservatives fall short.

Synonyms & Product Names

BIT goes by plenty of names. Beyond 1,2-Benzisothiazolin-3-One, chemical catalogs might call it Proxel GXL, Preventol BIT, or even simply Benzisothiazolinone. Different vendors push slightly tweaked formulations under their house brands, sometimes packaging them as “biocidal preservatives” or reference technical numbers tied to local registrations. This can create confusion for buyers, especially when local product codes or trade names mask the underlying chemistry, but a careful look at the CAS registry number helps people cut through the noise.

Safety & Operational Standards

Anyone running a drum of BIT needs to pay attention to safe handling. The dust can irritate airways and skin, so protective equipment—gloves, goggles, masks—becomes standard kit. Safety Data Sheets spell out the risk of sensitization: repeated contact sometimes triggers allergic skin reactions, especially among paint and detergent plant workers. Regulatory bodies set strict workplace exposure limits and push producers to switch over to closed systems where possible. In finished goods, allowed concentrations in consumer products often top out near 0.1%-0.2% by weight. Storage calls for a cool, dry spot, sealed packaging, and a regular eye out for leaks.

Application Area

BIT’s flexibility keeps it in demand. Large manufacturers load up emulsion paints, inks, and adhesives with BIT to keep microbes at bay. Home care companies use it in dishwashing liquids and detergents, pushing for longer shelf life even after opening. You’ll find it in construction sealants, wood preservatives, and process water treatments. Some researchers have even proposed it for oil and gas recovery, harnessing its bacteria-busting power in hostile, briny environments. Still, consumer demand for “low allergen” and “natural” products sometimes shrinks the list of acceptable chemical options, putting BIT’s future in a changing world up for debate.

Research & Development

Development teams have kept their eyes peeled for ways to boost BIT’s effectiveness or cut down on side effects. Green chemistry approaches look to renewable starting materials or greener solvents to make production cycles safer and cleaner. Some labs try to pair BIT with stabilizing co-preservatives, hoping to tackle bacteria and fungi with a single shot. Ongoing projects at universities and industry R&D hubs keep tinkering with BIT derivatives that show sharper specificity for resistant bugs or stretch the molecule’s compatibility with challenging formulas. Publications in the past five years detail new reaction routes and structure-activity relationships, hoping these tweaks might resolve emerging hurdles with regulation and consumer preferences.

Toxicity Research

Studies in the toxicology field weigh the risks and benefits. Straight ingestion or direct exposure rarely happens outside of industrial accidents, but skin sensitization crops up more often than some would like. Lab animals exposed to high doses can show organ toxicity, but approved uses in consumer products stick to concentrations well below threshold limits. Environmental scientists keep a close watch, tracking breakdown products and persistence in waterways after it gets washed down drains. Aquatic organisms sometimes show effects at higher exposures—a red flag for water treatment and discharge regulations. Everyone in the supply chain has a stake in making sure exposure stays within safe bounds for workers and for the broader public.

Future Prospects

BIT has held a reliable place in the world of industrial preservatives, but its future packs some uncertainty. Regulatory changes, especially in Europe, drive fresh risk assessment cycles every few years. Growing consumer pressure for greener preservatives nudges research toward biobased and biodegradable alternatives, but BIT can still outperform many of the gentler options on toughness and cost. Innovation in formulation chemistry might extend its reign, fitting BIT into materials that once resisted such “legacy” biocides. At the same time, stricter rules and public sentiment could one day prompt a hard pivot toward new solutions. Industry experience says adaptation matters, keeping one foot in today’s chemistry and an eye trained on tomorrow’s alternatives.

Why Do Manufacturers Use 1,2-Benzisothiazolin-3-One?

Shampoos, paints, detergents—most people trust that what comes out of the bottle will last. Mold, mildew, and bacteria often threaten that promise. 1,2-Benzisothiazolin-3-One, which experts call BIT, steps in quietly as a preservative, shielding products from spoilage and keeping them usable on shelves and at home.

Without tools like BIT, companies risk more than just bad batches. Spoiled goods can trigger recalls, put people at health risk, and punish trust in a brand. No surprise, then, that cost-conscious producers in Europe, North America, and Asia rely on BIT to avoid these headaches.

How Does It Work?

BIT keeps growing things at bay. In my experience, most people think about food preservatives—not many think about what keeps paint inside a can from turning nasty after a few weeks in a damp garage. BIT disrupts the tiny life cycles of microbes and fungi. No melty texture, no odd colors, no strange smells.

In paints and coatings, BIT helps fight the grime attracted to wet surfaces. Left untreated, surfaces with constant moisture—bathroom walls, kitchen counters, exterior woodwork—become perfect playgrounds for mold and bacteria. A small dose of BIT in the formula makes a long life possible for those bright finishes.

Where Can Someone Find BIT?

BIT goes far beyond household paints. Factory workers add it to liquid soap, wallpaper paste, adhesives, laundry detergents, and water-based cleaners. Some textile treatments carry BIT, giving uniforms and curtains more time before musty smells set in.

Daily exposure to BIT surprises many people. I once talked to a friend with a job in an industrial kitchen who didn’t realize the hand soap he trusted every day owed much of its freshness to these tiny chemical defenders. It doesn’t take much—usually less than one part per thousand—to make a difference.

Is BIT Always Safe?

BIT helps more than it harms, but it has caught the attention of scientists and regulators. Some people with sensitive skin may react to it, especially after repeated contact. In Europe, more complaints about allergic contact dermatitis pushed the chemical onto watchlists for soaps and cosmetics.

The European Chemicals Agency continues to research BIT’s health effects. The goal is to balance product safety with real-world needs. Long-term studies only reinforce the importance of following safety labels. Scrutinizing what reaches children’s skin or food surfaces always matters.

Pursuing Better Solutions

The search for alternatives remains strong. Green chemistry teams experiment with natural antimicrobials and aim for preservatives that serve the same purpose without possible side effects. Responsible brands now publish full ingredient lists, giving customers with allergies a degree of choice.

BIT has shown itself as a practical answer for fighting spoilage. Product safety relies on manufacturers keeping up with research and regulation, and regular folks learning why ingredients matter. If more people understand what BIT does in their products, the decisions in the store aisle become a little sharper.

Understanding What’s at Stake

Many of us use products every day without thinking too much about their chemical ingredients. Cleaners, paints, personal care goods—so many have a silent hero: the preservative. One such chemical, 1,2-benzisothiazolin-3-one (BIT for short), pops up frequently because it keeps bacteria and fungi in check. The question gets louder every time shoppers flip a bottle over and see a string of unfamiliar words: Is BIT actually safe on skin—or in the air we breathe around the home?

Health Concerns and Real Experiences

Dermatologists keep sounding the alert about preservatives. BIT’s often mixed in water-based products: latex paints, detergents, some cleaners, and sometimes cosmetics or wipes. That powder-fresh scent from a “clean” table might come with invisible chemical residue. I’ve definitely noticed dry skin after cleaning—and itchy patches that show up for no clear reason. Many friends who work in construction complain about red, irritated hands, especially after painting.

Scientific research backs those lived experiences. Studies out of Europe connect BIT exposure to allergic skin reactions. In fact, the German Federal Institute for Risk Assessment classifies it as a known allergen, and trade associations for cosmetics have called for restrictions on BIT in leave-on personal care products. If rinsed off thoroughly, temporary exposure in things like household cleaners or paint doesn’t look so bad for most people. Direct, repeated contact raises the risk of allergy, especially for folks with eczema or other sensitivities.

Safety Guidelines and Regulation

Europe draws a hard line: BIT is banned from European leave-on cosmetics and baby products. In the U.S., oversight isn’t as strict. The FDA leaves cosmetic preservative safety mostly to manufacturers. Many big brands, after seeing allergic reactions, started removing BIT from baby wipes and lotions. Paint industry workers face tougher challenges, spending hours with their hands in contact with paints and coatings loaded with preservatives. Bits of advice from experienced tradespeople matter just as much as regulations—just because it isn’t illegal doesn’t mean it can’t harm you. Gloves, good ventilation, and washing hands thoroughly after product use really do help keep skin safe from sensitizers like BIT.

Practical Solutions Moving Forward

Replacing BIT isn’t easy for manufacturers. Preservatives get picked for their strength—they beat back mold and bacteria even in humid bathrooms or steamy showers. Still, alternatives exist. Companies experiment with milder preservatives and natural extracts, though those come with their own hurdles around stability and shelf life. Consumers play a role just by reading labels, asking questions, and watching for any personal reactions. If products label BIT and skin acts up, people can switch to fragrance-free or BIT-free options, especially with cleaning or baby products.

Paying attention to everyday health and listening to your own body goes a long way. When someone notices itching, a rash, or any other odd reaction after using a cleaner or personal care product, it helps to check the label. A bit of caution with strong chemicals like BIT, especially for those with sensitive skin, is more than common sense—it’s how we stay safe in a world full of useful, but sometimes risky, ingredients.

Why Does Handling 1,2-Benzisothiazolin-3-One Matter?

1,2-Benzisothiazolin-3-One works as a preservative in paints, adhesives, and many household liquids. I’ve come across it in both industrial and laboratory settings. This chemical keeps mold and bacteria at bay, but it also causes problems if stored or used carelessly. I’ve seen workers get skin rashes after direct contact; bottles stored in sunlight sometimes degrade, and with leakage, nobody wants to breathe these fumes or touch contaminated surfaces. Chemicals like this have a place in our lives, but misuse piles up health, safety, and even environmental risks.

Proper Storage: Keeping People and Products Safe

1,2-Benzisothiazolin-3-One comes as a white to yellow powder or as a liquid formulation. I always stress the basics: keep the container in a dry, cool, and well-ventilated area. Temperatures above 40°C have caused some batches to break down or develop pressure, based on manufacturer incident reports. Direct heat or open flames in the storage area often start trouble; this compound isn’t extremely flammable, but under the right conditions, you’ll get toxic decomposition products, including sulfur oxides and nitrogen oxides.

Seal all containers tightly. Any moisture shortens shelf life and begins decomposition. Alongside the risks for the product, moisture allows bacteria and fungi to multiply, which ironically defeats the chemical’s primary job as a preservative. I have seen leaks in cardboard boxes or old plastic drums; these cases almost always lead to cleanup headaches, shelf loss, and unnecessary costs.

Handling: Reducing Direct and Indirect Exposure

Handling 1,2-Benzisothiazolin-3-One should never happen barehanded. Protective nitrile or neoprene gloves form a physical barrier against skin irritation. Even brief exposure can provoke redness, itching, and—after regular contact—sensitization. Lab goggles prevent splashes, and in places with a lot of dust, respiratory masks help keep harmful particles out of your lungs.

If a person drops some powder or spills solution on the ground, sweeping it up throws particles into the air. Moisten the area slightly or use dedicated chemical vacuum equipment. Simple water and soap won’t bind these particles strongly, so I keep chemical absorbent pads in my kit at all times.

Labeling, Segregation, and Disposal

Labels give everyone a heads-up, especially when transferring material between rooms or departments. Clear hazard pictograms and expiration dates save lives and prevent legal headaches. I always label in large print, and I never mix this chemical with strong acids or alkalis. Certain substances can trigger unwanted chemical reactions, releasing gases you don’t want near your face or coworkers.

Disposals matter just as much. Municipal drains cannot handle this product; city treatment plants do not always break down these compounds thoroughly. I collect spent material in a separate waste drum and work with licensed waste handlers, keeping documentation for audits. Neglecting this step leads to fines, contaminated soil, and angry neighbors—as seen in news stories from regions with weak hazardous waste control.

Solutions for Safer Use

Training workers, marking storage areas, and keeping up-to-date Safety Data Sheets handy stay at the core of a responsible workplace. Regular inspections and fast response when leaks or damage show up can head off most risks. I value a culture where staff feel comfortable reporting spills or asking questions about protective equipment; this mentality keeps everyone safer.

Direct Contact Brings Real Trouble

A lot of folks handle cleaning supplies or paints without thinking twice about the chemicals inside. I remember working in a factory one summer, where containers sat stacked with all sorts of mysterious ingredients. 1,2-Benzisothiazolin-3-one, better known as BIT, ended up stamped on many of those ingredient lists. People rarely imagine much harm from touching a paint can, but BIT doesn’t belong on bare skin. Even brief contact causes itching, burning, and even blisters in some people. In one case, I watched a coworker develop red, raw hands after a morning spent mixing buckets. Turns out, BIT ranks as a strong skin sensitizer. You might wash it off and think nothing of it, but the next time brings a rash, and it only gets worse with repeat exposure.

Breathing the Vapors Isn’t Harmless

There’s something overlooked about fumes when people work inside stuffy rooms. BIT turns up in industrial settings where ventilation rarely keeps up. Inhaling its dust or mists doesn’t just trigger a sneeze. It leads to sore throats, coughing and in some cases, even asthmatic reactions. Some research shows people in jobs that use a lot of BIT report breathing problems over time. Ongoing low-dose exposure can set off the immune system much the way skin contact does, making allergies and asthma more common. Paint shops and factories using biocidal products face this more often than office buildings, but it pays to pay attention to that subtle tang in the air.

Lasting Health Effects

Hospitals and poison control centers have logged serious allergic responses stemming from BIT use. It’s more than a local rash—swelling, hives, or breathing trouble land some people in the ER. A report in the journal Contact Dermatitis found BIT played a role in a rising number of hand eczema cases among cleaners, nurses, and janitors. The pattern seems strongest where BIT turns up in hand soaps or surface wipes without clear labeling. Not everyone is sensitive at first, but repeated run-ins raise the odds. Scientists have even placed BIT on the EU’s shortlist of substances of very high concern for skin sensitisers.

Environmental Spillover

BIT doesn't stay put after use—it slips down the drain with every mop bucket and cleaning rag. Some studies trace it right to city wastewater, where it can stick around longer than people think. Once released, it may cause trouble for aquatic creatures. Toxicologists point to algae, crustaceans, and fish that react at concentrations seen in some treated water. The EU has flagged BIT as a risk for aquatic ecosystems if use rates climb unchecked. Preventing run-off by capturing cleaning water or reducing unnecessary use helps keep those risks lower.

Better Labels and Smarter Rules

Labeling hasn’t kept up with the spread of BIT. Consumers rarely spot clear warnings, despite its growing use in things like liquid detergents, paints, and ink. The European Chemicals Agency recommends listing potential allergens in all personal and cleaning products at amounts above 0.05%, a move that would help sensitive folks steer clear. Companies that phase out BIT show it’s possible to clean up without clinging to old ingredients. For now, wearing gloves, airing out rooms, and smart purchasing choices matter just as much as good policy—speaking from plenty of years spent elbow-deep in one industrial project after another.

Understanding the Chemical

1,2-Benzisothiazolin-3-one, known around factories and labs as BIT, shows up in everything from paints to dish detergents. Manufacturers lean on it for its tough antimicrobial punch. It halts mold, bacteria, and more from wrecking products before they hit your home. Most folks likely touch BIT in everyday life without a clue about its impact. Yet the question grows louder: what happens to BIT after it washes down the drain or sits in the landfill?

Environmental Concerns with BIT

From my own years working with chemistry in product development, a red flag usually waves once a potent antimicrobial gets paired with water treatment systems. These chemicals do not always break down quickly. BIT acts the same way. It resists rapid breakdown in the environment because it was designed to survive in water-based products. So, instead of vanishing, it lingers. Environmental research has tracked BIT in surface water, especially near industrial run-off sites. Lab studies from Europe and Asia point out that BIT doesn't dissolve easily in water or soil. When exposed to light in real ponds or lakes, it still sticks around longer than “green” alternatives like essential oil-based agents.

Is BIT Biodegradable?

People who work in wastewater treatment see all kinds of synthetic additives flow through the system. BIT turns up routinely in those influents. Data from German and Canadian water studies show that less than half of BIT breaks down by standard municipal treatment. What's left moves out with treated water, either slipping into rivers or rejoining other systems. Scientists running aerobic biodegradation tests see BIT degrade slowly, with some breakdown after weeks, not days. With so many chemical inputs competing for bacteria's attention, BIT’s long half-life stands out.

Bioaccumulation Risks

BIT does not build up in fish to the same degree as long-chain hydrocarbons or heavy metals. But incomplete breakdown still raises risks for aquatic critters. BIT’s toxicity toward algae, Daphnia, and aquatic plants remains moderate, but persistent presence shifts the balance over time. These traces can travel up the food chain, and even low doses add uncertainty to water safety. Regulatory agencies in the EU have flagged BIT for further review because of these slow-breakdown traits and potential chronic toxicity.

Moving Toward Safer Solutions

If we want consumer goods to last without using BIT, the hunt for safe replacements cannot be cut short. Some firms test enzymes and fermentates sourced from food-grade cultures. These break down more easily, but often cost more or don’t last as long in storage. Advocating for lower-load uses, better rinse-off and capture at source (especially in industrial settings), and investing in improved treatment stages at sewage plants could limit BIT’s journey into rivers and lakes. In my own team’s work, even partial swaps for milder antimicrobials made a difference in effluent analysis.

Why the Decision Matters

Frontline makers and regulators carry the responsibility of balancing product safety with real environmental impact. No agency has a perfect fix just yet, but transparency about BIT’s behavior provides a launching point. Keeping toxic buildup in check requires not only chemical tweaks at the factory but also better monitoring downstream. Along the supply chain, the choices made do ripple out—first at the tap, eventually into streams where the smallest creatures end up wrestling with leftovers we did not see.