1,1,2-Trichloroethane: Commentary on Its History, Application, and Future

Historical Development

Long before everyday chemicals lined factory shelves and the back rooms of industry, 1,1,2-trichloroethane was born out of necessity during a period marked by intensive growth in chemical manufacturing. Its rise in the mid-20th century owes much to the surge in demand for chlorinated solvents and intermediates. Early producers, recognizing the need for efficient chemical syntheses and precision in industrial clean-up, found this molecule provided both. Chemical pioneers created industrial-scale synthesis routes that did not simply rely on nature’s bounty, but rather on ingenuity and repeated trial and error. The evolution in the technology reflected how chemical plants gradually cut down on waste and honed safety standards, but the risk was always present, giving workers a front-row seat to the real impact of working with volatile organic compounds.

Product Overview

1,1,2-Trichloroethane, known for its role as both solvent and intermediate, forms the backbone of processes where stronger chemicals would cause too much damage or too much cost. In many plants it gets stored in rust-resistant drums, stowed away from sunlight and sparks, and used during precise cleaning steps or chemical conversions. I remember seeing the thick gloves and goggles workers wore before handling the stuff; there’s a sense of respect for any material that carries serious health warnings and sharp odors.

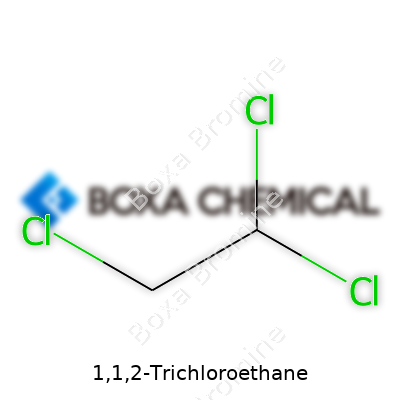

Physical & Chemical Properties

This colorless liquid tends to catch folks off guard, mainly because its sweet, chloroform-like smell can fill a lab before anyone notices a drip. It boils at about 113 °C, and its density puts it heavier than water, causing it to sink rather than float in spills. Its molecular formula, C2H3Cl3, wraps three chlorine atoms around an ethane backbone, boosting its reactivity in substitution reactions yet making it stubbornly persistent in the environment. Unlike lighter chlorinated solvents, it clings to surfaces, resisting evaporation at room temperature, but it certainly doesn’t hesitate to work its way into water tables if leaks happen near ground or drains.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Industrial supply drums of 1,1,2-trichloroethane usually come with meticulous safety labels, hazard pictograms, and clear technical grades. Most commercial stock comes at a purity exceeding 99%, since lower grades show up as brownish tints or harbor dangerous byproducts like 1,2-dichloroethene. Clear, concise chemical safety sheets outline flash points, recommended storage temps, and prescribed first aid. Proper labeling goes a long way, but only careful training and diligent maintenance keep transportation accidents at bay.

Preparation Method

Production often starts with acetylene, which undergoes hydrochlorination to yield vinyl chloride. Chemists then introduce more chlorine under controlled heat, swapping hydrogen atoms for chlorine to yield 1,1,2-trichloroethane. Each batch run requires precise controls on temperature and flow rates so as not to tip toward unwanted isomers or byproducts. Once the reaction concludes, distillation separates the desired product, which leaves behind heavier residues and cuts down on contamination. Every technician involved can attest to the toxic fumes and the need for ample venting and recirculation filters.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

Lab work with 1,1,2-trichloroethane usually revolves around its use as a starting point for synthesizing other chlorinated organics. Exposure to reactive metals like zinc or sodium can strip away chlorines, leading to less-chlorinated ethanes or vinyl compounds. Add in strong bases, and the molecule can lean toward elimination reactions that form vinylidene chloride. Some research teams have explored how the compound reacts under photolysis, which holds some promise for more benign environmental breakdowns, but the stable C-Cl bonds offer plenty of resistance to most treatment methods.

Synonyms & Product Names

Go to a chemical supplier, and you may see product names like Ethane, 1,1,2-trichloro-; Beta-trichloroethane; Vinyltrichloroethane; or even Dow’s proprietary labels from earlier eras. All point to the same compound, yet in patents and import records, each variant title can cause confusion unless you’ve spent years deciphering the lingo of chemical registries.

Safety & Operational Standards

Few chemicals command as much caution as this solvent. Workers rely on full-face respirators, chemical-resistant gloves, and splash-proof suits during heavy-use operations. Factories implement strict exposure limit monitoring, constant air testing, and regular training updates after any incident. Accidental contact with skin leads to rapid irritation, while breathing in the vapors quickly causes dizziness, headaches, or worse, signs of nerve damage. The U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration caps permissible exposure limits at 10 ppm, reflecting the compound’s toxicity even at low doses. Facilities develop contingency spill kits, dedicated ventilation, and first-responder stations for good reason.

Application Area

Industrial users reach for 1,1,2-trichloroethane as a solvent in cleaning delicate metal surfaces, removing grease from military or aerospace parts, or degreasing intricate machinery. At its peak, companies employed this solvent in large-scale manufacture of 1,1-dichloroethene and other intermediates. Paints and adhesives sometimes required its solvency power when no other chemical did the job without riskier residues, but regulatory and market shifts have shrunk its uses over the years. Having watched plants phase it out in favor of safer alternatives, you can spot which shops prioritize worker health and which stay stuck in familiar—if hazardous—routines.

Research & Development

Academic and private labs investigate alternative synthesis routes and breakdown techniques for 1,1,2-trichloroethane, hunting for better environmental outcomes and lower risk profiles. Researchers track the molecule’s breakage products as they try to predict and mitigate groundwater contamination, while others evaluate novel catalysts for selective chlorination. Newer efforts also target non-chlorinated alternatives for industrial cleaning, aiming to eventually sideline classically toxic solvents from routine use. Grant funding often favors green chemistry, making it tough for projects that purely extend the old solvent’s reach to gather steam.

Toxicity Research

Studies dating back decades link chronic exposure to liver and kidney problems, nervous system disorders, and possible carcinogenic effects. Animal research and epidemiology both highlight how careful companies must be about ventilation, containment, and medical monitoring—especially when used in enclosed areas. The Environmental Protection Agency designates it as a hazardous air pollutant, and regulations require any site using or producing it to track and limit emissions closely. Cleanup of legacy contamination, especially around industrial sites, costs millions and takes years, reflecting a growing public intolerance of unchecked chemical pollution and the clear evidence of real human health outcomes.

Future Prospects

Few see a bright future for 1,1,2-trichloroethane outside tightly regulated, niche chemical syntheses. With most industries shifting toward greener alternatives or closed-loop chemical recycling, the solvent’s role shrinks each year. Regulatory pressure will likely intensify, nudging slower companies to upgrade processes or pay out for cleanup and litigation. Researchers and plant managers who once depended on this chemical have the opportunity to transition toward safer, sustainable options, passing along hard-learned lessons on containment, emergency planning, and environmental stewardship.

The Role in Industrial Solvents and Cleaning

Factories and workshops across the globe used 1,1,2-trichloroethane as a cleaning agent for metal and machine parts. If you’ve ever seen a car mechanic’s shop or a metal fabrication plant, you probably noticed grease and oily grime building up around tools, gears, and machinery. Workers needed something tough enough to break down these substances, and this chemical certainly did the job. Its strong solvency power allowed industries to get metal parts spotless before painting, welding, or assembling. Large manufacturers counted on its ability to dissolve stubborn oil and waxes that water alone couldn't touch.

Dry cleaners and electronics assembly lines also took advantage of this solvent power. Printed circuit boards, before getting assembled into computers and phones, collected dust and flux residue. Wiping these boards with a strong solvent helped achieve a higher standard of cleanliness, which improved reliability and performance in the finished products.

Key Intermediate in Chemical Synthesis

1,1,2-Trichloroethane serves more than just as a rinse for dirty equipment. It plays a key role as a chemical building block, being involved in the production of other chemicals. Factories use it to create vinylidene chloride, the key ingredient found in some plastic wraps and food packaging. Without 1,1,2-trichloroethane, many of these products wouldn’t exist in their current form. Knowing this connection sheds light on how important base chemicals are for the supply chain that leads to everyday items sitting on grocery shelves.

It also finds use in creating substances like 1,1-dichloroethene. These materials form the backbone of specialty plastics used in piping, wires, and barrier films. My time visiting a polymer plant highlighted how a single bottle of colorless liquid could trigger the start of huge production runs, channeled through reactors that churned out the plastics companies needed for modern packaging and insulation.

Spotlight on Environmental and Health Concerns

Growing awareness about toxic chemicals has shifted the approach industries take to 1,1,2-trichloroethane. Workers exposed to high concentrations risked nervous system effects, dizziness, and even longer-term health problems. Communities started noticing contaminated groundwater near manufacturing sites, a direct risk to health when water wells turned up traces of this compound. These environmental realities raised tough questions. As with many older industrial chemicals, its benefits came tangled with risks that regulators and companies couldn’t ignore.

Exploring Safer Alternatives and Solutions

Shifting away from 1,1,2-trichloroethane comes down to a mix of government guidance and industry innovation. The Environmental Protection Agency placed tighter restrictions on its use, pushing for closed systems that reduce worker exposure and emissions. Some manufacturers already switched over to greener solvents such as aqueous-based solutions or engineered blends that don’t carry the same environmental baggage. Simple actions—like upgrading to better ventilation and protective gear—helped lower risks immediately, even before full replacements reached the market.

Investing in research pays off here. Public agencies and companies have funded safer chemistry, finding new solvent systems that handle metal degreasing or electronics cleaning without long-term environmental fallout. Seeing this shift in real time offers a glimpse of how science, regulation, and practical engineering come together to solve real problems.

What Kind of Chemical Is 1,1,2-Trichloroethane?

1,1,2-Trichloroethane may sound like something that stays in the lab, but it appears in more places than most of us notice. This chemical used to turn up in industrial cleaning, as a solvent, or in making vinylidene chloride. At first whiff, that sharp, sweet smell makes it obvious something unnatural is in the air. The clear liquid vaporizes quickly, and that volatility counts for a lot—especially when thinking about how easy it moves from workplace spills to the air we breathe.

Direct Exposure and Health Problems

Getting too close to 1,1,2-Trichloroethane carries a punch: harsh on the lungs, eyes, and skin in the short term, and much worse in the long run. Even a short breath from a high concentration can bring on headaches, dizziness, or even nausea. Contact with skin might leave painful burns. In factories, workers have gotten sick after regular exposure. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency points out that repeated contact with this solvent can damage the liver and kidneys. That’s the big concern—ongoing, small exposures add up, and most folks never realize their body is having a tough time keeping up.

Carcinogenic Risks: What Does the Science Say?

Long-term worries ramp up with any chemical that earns a possible carcinogen tag. The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) classifies 1,1,2-Trichloroethane as a Group 2B agent, which means a possible cancer risk for humans. Lab studies using animals found higher rates of liver and kidney tumors after regular exposure. Science keeps studying this for better answers, but the caution signs are up and public warnings from OSHA and NIOSH fill a page.

How Does It Get Into the Environment?

Not all of the chemical gets locked inside factories. Some escapes into water or soil through improper disposal. In city water reports, trace levels sometimes pop up—enough to ring alarm bells for people relying on wells near landfill sites. Drinking water standards stay tight to protect the public. The EPA sets the maximum contaminant limit at just 0.005 milligrams per liter. After a few stories in the news about neighborhoods with toxins in their groundwater, it makes sense to worry about these numbers, even in small amounts.

Protecting Workers and Neighborhoods from Exposure

Most would agree: no one should have to risk health because of chemical leaks or a lack of safety at work. Factory safety teams use sealed machinery, exhaust fans, and regular air checks to stop exposure before it starts. On a personal level, workers put on gloves and respirators every day. Federal rules push companies to report spillages and keep use below certain limits, but enforcement sometimes falls behind what the law actually says. Community groups keep watch and push for more cleanup in places where these chemicals have hung around too long.

What Needs to Change?

Health and safety take ground-level work. Regular water testing, better site cleanup, and investment in safer chemical alternatives should rise above profits for manufacturers. People living near old dump sites have every right to clear information and rapid help. In my own town, neighbors demanded testing when a strange odor started coming from a drain—persistence got an environmental crew to check our water and clean up a leaky barrel site. Standing up for health may sound like a hassle, but it keeps places safe for families and workers. Facts show that substances like 1,1,2-Trichloroethane hang around for years, so the safest bet remains prevention and transparency, not just quick fixes or promises.

Why 1,1,2-Trichloroethane Requires Respect

Folks in many labs and factories work with solvents every day. 1,1,2-Trichloroethane gets used for cleaning, degreasing, and as a chemical building block. It's clear and doesn't smell too strong, so it might not seem all that threatening. That’s where people get it wrong. The science is clear: breathing in its vapors can mess with your nervous system and irritate your lungs, and you don’t want this stuff soaking into your skin. I’ve seen sloppy storage lead to leaks and unexpected headaches—sometimes worse.

Storing Trichloroethane: It’s Not Like Storing Paint Thinner

A lot of folks treat storage as a footnote, but I’ve found that little shortcuts add up and bite back. Put this chemical in a steel drum or approved glass bottles. Plastic seems like a quick fix, but it won’t stand up over time. Always keep those containers sealed—don't figure you’ll come back and cap it later. I once saw an open container turn a storeroom into an unbearable headache zone.

Temperature matters. A hot storeroom will make those vapors come out faster, and you do not want a flammable situation creeping up on you. Find a cool, dry spot away from sunlight or heat vents. Letting it share space with acids, alkalis, or any oxidizers is trouble, too—the chemistry just doesn’t mix.

Ventilation and E-E-A-T: A Real Risk and a Real Solution

Walking into a tight storage space with no airflow cranks up the risk. I recommend a dedicated, well-ventilated area, not a closet in the back. Fans or local exhaust hoods pull vapors out and bring clean air in. I learned early on that sniffing chemicals in the morning means policies need fixing.

Good ventilation lines up with Google’s E-E-A-T principles. Scientific evidence and experience agree: proper airflow lowers exposure and cuts health risks for workers. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health backs up this advice, pointing to reduced headaches, nausea, and other symptoms when airborne solvent levels drop.

Personal Protective Equipment: No Excuses

Some folks see gloves and goggles as optional. Until you get a splash in the eye or on your skin. You don’t want that. I use chemical-resistant gloves, goggles, and a proper lab coat—not dollar-store gear. Masks with organic vapor cartridges aren’t just a legal box to check, they’re a direct shield for your lungs. Laughing it off leads to bad days.

Emergency Planning: Because Things Do Go Wrong

Trichloroethane spills or leaks make a mess and spread fumes fast. Know the right spill kit: absorbent pads, inert materials, and the right containers for cleanup waste. Get emergency shower and eyewash stations ready and keep the paths clear, not blocked by empty boxes. Everyone who handles chemicals in a shop or lab deserves regular training. Your gut might tell you what’s wrong, but practical drills save time and lives.

Label every single container with bold, clear signs—never trust someone will “just know.” Waste belongs in a certified drum, never down a drain.

Better Attention Means Fewer Accidents

Treating 1,1,2-Trichloroethane with respect pays off. We owe it to each other to put tried-and-true practices ahead of convenience. Taking shortcuts means paying a bigger price down the line. I’ve seen both careful and sloppy workplaces, and I'd take careful every time. Real attention to storage and handling protects people, places, and reputations—no short supply of reasons to get it right.

The Story Behind the Chemical

You see 1,1,2-Trichloroethane on safety data sheets for decades. The name rarely means much unless you work with cleaning solvents, adhesives, or refrigerant manufacturing. Companies have found it handy thanks to its ability to dissolve oils and greases. But just like many legacy chemicals, its performance comes with baggage—and it’s not just a workplace hazard.

What Happens Outside the Factory Fence?

Spills, leaks, and venting from old industrial sites put 1,1,2-Trichloroethane into groundwater and soils. Once there, it lingers, moving slowly but surely through soil and water. In one case I helped with, an old barrel—long forgotten—corroded enough to let this liquid drip into clay soils behind a metal shop. Residents nearby didn’t know, but wells tapped into that same underground water long after the plant closed.

Chemically, this solvent breaks down into other troublemakers. It forms 1,2-dichloroethene and vinyl chloride, both of which pack their own toxic punch. If left to react under sunlight or with bacteria, these breakdown products travel further. The EPA reports groundwater plumes containing trichloroethane and related chemicals at multiple Superfund sites. The stuff doesn’t evaporate quickly or degrade in weeks—persistent is the right word.

Ecosystems Pay the Price

Fish and amphibians that swim or lay eggs in contaminated water take up 1,1,2-Trichloroethane through their gills and skin. Researchers have recorded stunted growth and lowered reproduction rates in fathead minnows exposed to concentrations like those measured at some waste sites. Sediments keep this chemical locked away, but changes in water flow—spring flooding, for instance—release it back out, exposing new life each year.

Plants try to pull it up with their roots but can’t break it down completely. Vapors vent from soils and can creep into basements, a process called vapor intrusion. I’ve seen homeowners breathe in levels ten times higher than outdoor air without realizing it.

How People Get Exposed—and Why It Matters

Inhaling vapors or drinking contaminated well water means direct exposure. Short-term, people get dizzy, feel sick, or suffer irritation. Over years, studies link exposure to problems with the liver, immune system, and possibly even cancer. The International Agency for Research on Cancer ranks 1,1,2-Trichloroethane as a possible human carcinogen—which isn’t comforting news for families living near industrial zones.

What Can We Do About It?

Cleanup isn’t easy. Digging up contaminated soil and treating it with heat works, but costs pile up quickly. Pumping out groundwater and running it through carbon filters drags on year after year. Bioremediation—letting bacteria chew up the solvent—offers hope at slow-moving sites, but progress depends on weather, temperature, and chemical soup underground.

We need better ways to track and prevent leaks, especially old drums and forgotten waste pits. Regulations exist, but monitoring and transparency matter more. Engineers designing factories today know the risks and plan for secondary containment, but legacy sites lack these protections.

Public right-to-know laws have helped shine a light on contamination. People pressured cities and states to sample wells, and new sensors now give real-time data on chemical leaks. Replacing old products with less persistent chemicals makes a difference, too, though the shift takes time.

Looking Ahead

Experience working with trichloroethane pollution convinces me that local action wins out over promises. Residents checking their water, plant managers keeping inventory, and scientists searching for new cleanup tools will turn things around more than waiting for sweeping national fixes. With every generation, we learn more about pollutants like this—and can insist on changes that work.

Why 1,1,2-Trichloroethane Matters

1,1,2-Trichloroethane stands out among industrial chemicals as a solvent that can quickly become a health risk if not respected. Folks working in labs or factories know to take it seriously partly because the liquid’s vapors can cause everything from dizziness to liver damage. Small spills can turn into big problems without quick action, and skin or eye contact can load up the body with toxic chemicals faster than people think.

Immediate Actions for Spills

My time helping clean up after a lab mishap taught me one thing: speed and confidence matter more than theory. If you find 1,1,2-Trichloroethane on the floor, get folks out of the area who aren’t needed, then let people know what happened. Anyone handling the cleanup needs gloves—nitrile, not latex—a splash-resistant apron, and goggles that seal around the eyes. Cotton clothes trap fumes, so chemical-resistant gear gives a heavier dose of security.

The substance evaporates fast, so open a window or flip on a fume hood to clear the air. A spill sock surrounds the liquid and stops it from spreading under doors or into drains. Absorbent pads or clay granules soak up liquid. I’ve watched teams scoop soaked material into a steel drum, then seal it tight for the hazardous waste haulers. After, the spot gets scrubbed down with soap and water—plain paper towels just spread small amounts wider, so skip them. Double bag any rags before tossing them out.

If You Get 1,1,2-Trichloroethane on Your Skin, Eyes, or Breathe It In

A colleague once splashed his wrist. Quick thinking meant off went the watch, up went the sleeve, and his whole arm hit the emergency eye wash station. At least fifteen minutes rinsing cold water removes most of the stuff; warm water speeds up absorption, so avoid it. Most people only remember their eyes once the sting sets in, but the faster you flush, the less likely you’ll deal with lasting damage.

For inhalation, a well-fitted cartridge respirator kept me safe during a warehouse leak. If someone’s dizzy or coughing, help them get outside for fresh air. Don’t hang around hoping the headache passes—the chemical’s trickier than that. If symptoms don’t fade, doctors can check liver markers and look for signs of toxic buildup.

Building Safer Spaces

Reducing risk comes down to what a jobsite lets people do every day. Chemical spill kits in reach cut stress when every second counts, and clear emergency plans get everyone on the same page. Safety showers and eye washing stations matter; so does refresher training that uses everyday language instead of just policy talk. Culture shifts fastest when new hires see everyone from management down using gloves, goggles, and monitors.

Stronger Prevention Saves Trouble Later

Labels, up-to-date Safety Data Sheets, and honest communication have pulled more than one team out of trouble. Ventilation costs more than cutting corners but saves headaches, and real-time gas monitors tell the truth when noses can’t. I’ve seen how regular checks—on both equipment and habits—stop mistakes turning serious.

1,1,2-Trichloroethane can’t be wished away, but practical habits, quick thinking, and respect for its danger make a routine day at work safer for everyone.