1,1,2,2-Tetrachloroethane: Full-Spectrum Review

Historical Development

The story of 1,1,2,2-Tetrachloroethane traces back to the golden years of industrial chemistry in the late 1800s. Manufacturers hunted for substances to clean machinery, thin paint, and serve as chemical intermediates. Chemists first produced it by combining acetylene and chlorine, fueling the rise of cleaning products and certain pesticides through the 20th century. Once, its use filled industrial floors, laboratories, and even made its way into consumer products. Regulatory attention grew as the toxic effects became clear, placing the spotlight on worker health and driving the need for safer practices. The chemical belongs to the broader clan of chlorinated solvents that shaped much of early synthetic chemistry, leaving a complex legacy that mixes necessity with caution.

Product Overview

This chlorinated hydrocarbon looks like a colorless, heavy liquid, with a whopping chemical stability under many conditions. Its strong sweet odor, reminiscent of commercial cleaning agents, gives away its identity before any chemical test. People found it effective for degreasing and as a solvent when few alternatives matched its power. Anyone familiar with the sharp, heady smell of old workshops might have caught a whiff of this liquid or its cousins. Over time, use narrowed as industry and science understood the health risks, shifting reliance to chemicals with better safety records.

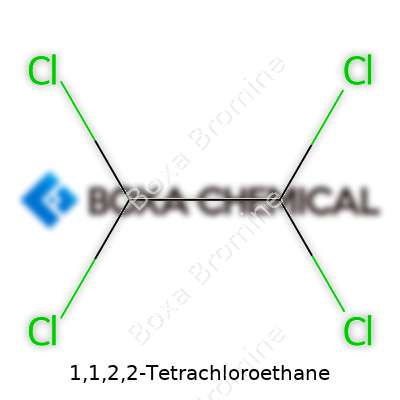

Physical & Chemical Properties

1,1,2,2-Tetrachloroethane stands out with a boiling point around 146 degrees Celsius and a freezing point near -35.4 degrees Celsius. Its density, higher than water, means a dropped sample sinks fast in most lab vials. This liquid resists ignition, avoids mixing with water, and dissolves grease and oils with remarkable tenacity. Its molecular structure — C2H2Cl4 — lines up chlorine atoms along the carbon backbone, which adds to its chemical stability. Despite not burning easily, it can break down under high heat or ultraviolet light, often producing toxic byproducts like hydrogen chloride and phosgene. With vapors that weigh more than air, exposure risks rise in poorly ventilated spaces.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Regulators require clarity in labeling due to its toxic profile. Product drums arrive stamped with hazard codes, UN numbers, and detailed storage instructions: cool, dry, away from direct sunlight, and locked against unauthorized access. For industrial handling, labels state purity (often above 99%), possible stabilizers, and a full list of safety information, including eye and respiratory protection requirements. Shipping this chemical, whether across borders or states, brings a stack of regulatory paperwork reflecting the dangers it poses. Each container warns against skin contact, prolonged inhalation, and careless disposal, reinforcing the health and environmental stakes.

Preparation Method

Manufacturing starts with chlorination of ethylene or acetylene. In one classic reaction, passing a steady flow of dry chlorine gas over liquid acetylene with cooling yields tetrachloroethane, usually alongside trichloroethene and other side products. Managing reaction temperature and chlorine flow controls the end product ratio. Crude mixtures undergo fractional distillation, pulling off fractions at specific temperatures. Industrial plants operate with strict containment to capture unreacted gases—an accident here could turn serious quickly, given the corrosive and toxic nature of the reagents. The process stands as a reminder that early methods, once seen as marvels of engineering, demand ongoing improvements in safety.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

Few chemicals show more versatility with halogenation chemistry. 1,1,2,2-Tetrachloroethane serves as a starting material for synthesizing trichloroethylene and tetrachloroethylene. Applying heat or catalytic conditions, it dehydrochlorinates, dropping hydrogen chloride and forming these valuable industrial solvents. Strong bases provoke further transformations, peeling off chlorines and infusing the backbone with new functional groups. In organic synthesis, it pops up as a building block for dyes, pharmaceuticals, and specialty lubricants. The chemistry circles back to industrial feedstocks, although tighter regulations have trimmed its appeal compared with newer, less hazardous alternatives.

Synonyms & Product Names

Chemists rattle off its aliases: Tetrachloroethylene (not to be confused), Acetylene tetrachloride, Ethane, 1,1,2,2-tetrachloro-, R-130, or S-tetrachloroethane. Commercial safety data sheets list these names alongside registry codes such as CAS 79-34-5. Historic documents sometimes span a page with variant titles, showing a time when naming standards flowed with the interests of manufacturers and national chemical catalogues. Keeping these names clear matters—not all tetrachloroethanes behave the same way, and a slip in ordering can mean delivering a toxic shock rather than a safe solvent.

Safety & Operational Standards

Every company using 1,1,2,2-Tetrachloroethane keeps a close eye on engineering controls and protective equipment. Even low levels of vapor sting the eyes and nose, while chronic exposure causes damage to liver, kidney, and the nervous system. Modern safety protocols call for full-scale ventilation, chemical-resistant gloves, and respirators. Handling policies limit the risk of spills or leaks, and lockout controls keep unauthorized workers safe. Anyone cleaning up a spill follows prescribed routes for containment, neutralization, and waste disposal, documented in Material Safety Data Sheets. Facility managers invest as much in emergency planning as they do in actual product handling, sometimes learning from near-misses that linger in memory.

Application Area

Though its heyday has passed, certain industries still tap its powerful dissolving ability for specialty cleaning and extraction work. It finds limited roles in the manufacture of other chemicals, sometimes as a reaction medium for particularly stubborn starting materials. Niche laboratories—especially those working on legacy processes—keep stocks for reagent use, watching expiration dates with care. Its decline stems more from hazard awareness and substitutes like less toxic hydrocarbons or green solvents than a lack of performance. Places where environmental regulations run looser may lag behind, but the broader trend points toward minimizing reliance except where no substitute fills the need.

Research & Development

Recent research underscores detailed analysis of degradation products and exposures linked to accidental releases. Analytical chemists refine detection techniques, looking for parts-per-billion sensitivity in soils and water. Predictive toxicology labs design safer chemical alternatives by studying how its molecular structure triggers biological effects. A handful of studies dig into creative uses: synthesizing high-value chlorinated intermediates, probing its fate in advanced degradation treatments, or unraveling reaction kinetics that apply to safer solvents. Industrial safety teams keep updating protocols to stay ahead of changing standards, while environmental scientists look for bioremediation solutions after contamination.

Toxicity Research

Extensive toxicity trials make 1,1,2,2-Tetrachloroethane a benchmark for studying organochlorines’ health impacts. Acute exposures bring on nausea, dizziness, and respiratory stress—and in high doses, risk of coma or death. Chronic cases highlight liver fibrosis and increased cancer risks in rats and mice, outcomes that fueled stronger regulatory oversight. Researchers frame much of this work around stories from exposed workers who developed symptoms after years of routine contact. In the environment, it barely breaks down, leaking into groundwater tables near landfills or chemical plants. The compound’s stubborn persistence and the way it accumulates in living tissue continue to draw urgent study, both for public health and cleanup strategists.

Future Prospects

Few expect a comeback for 1,1,2,2-Tetrachloroethane as a mainstream solvent—too much evidence stacks up against it regarding safety and the environment. Most countries pushed it off center stage, encouraged by safer, more biodegradable alternatives that carry a lighter regulatory burden. Researchers innovate in greener solvents, exploring bio-based chemicals and processes that eliminate chlorinated waste. Environmental cleanup projects—using bioreactors, advanced oxidation, and containment—offer hope for dealing with legacy contamination. Chemical engineers continue searching for routes that deliver needed performance without the risks, motivated by both strict regulations and hard-won lessons from past exposure. The chemical’s tale reminds us all that industrial advances bring real costs and real responsibilities, shaping how science and society think about progress and risk.

What 1,1,2,2-Tetrachloroethane Means for Industry

A lot of folks hear the name 1,1,2,2-Tetrachloroethane and think of a lab experiment rather than something with a real-world purpose. Yet, for decades, this chemical put in plenty of work behind the scenes in factories, product plants, and research setups. For me, looking at what drives its use, there’s always a story about why a chemical sticks around—or fades away.

Past and Present Uses in Manufacturing

Factories once favored 1,1,2,2-Tetrachloroethane as a solvent. It cuts through grease, dissolves organic material, and helps get mixtures just right. Sure, paint and varnish makers relied on it to smooth out their products, and the textile world leaned on its cleaning power. So did labs, where it made a name as a starting point to whip up other chemicals, including vinyl chloride—the stuff that leads to PVC plastic.

In my experience, visiting older workshops and talking to workers, I have seen how common it was to find barrels bearing a “tetrachloroethane” label. Technicians would stretch out gloved hands, wary of spills, because of all the warnings in the safety manuals. The chemical cuts deep as a degreaser, better than plain soap or everyday cleaners.

This chemical also played a role in creating pesticides and certain flame retardants. It helped strip and clean engine parts and electronic components, too. Realistically, plenty of things have changed since those days. Workers today usually reach for less toxic choices, but the history lingers.

Health and Environmental Warnings

Anyone who’s spent time reading hazard notes on 1,1,2,2-Tetrachloroethane sees the red flags. The Centers for Disease Control points out risks of liver and kidney damage, dizziness, and breathing trouble after enough exposure. In my view, stories from people who worked around these chemicals matter. Many older workers describe rashes, headaches, or worse, tied to poor ventilation and plain old oversight.

Leaking containers and improper disposal led to groundwater contamination in some communities, with lasting consequences. I have spoken with neighbors in affected towns, most of them angry and wary, waiting for cleanup plans to finish. Concerns about cancer and chronic health problems create pressure to keep close watch on this chemical.

Outlook: How to Stay Safe and Find Smart Alternatives

Some regulations, like those from the EPA and OSHA, set strict rules about using and disposing of 1,1,2,2-Tetrachloroethane. Workers need gloves, goggles, strong exhaust systems. Training days cover spill scenarios and first aid. Companies invest in updated equipment that seals away fumes or switches to less harsh cleaners whenever they can. Younger engineers I meet clearly favor modern 'green chemistry' methods, which aim to skip toxic stuff altogether.

Finding better options means sharing info—between managers, labor groups, and communities. Even at a local hardware store, shoppers see warning stickers and material-safety sheets. The push for safer chemicals rarely makes headlines, but in the places where people build, clean, and repair, it’s a big deal. Scrapping risky chemicals in favor of safer methods protects more than just workers. It shields families and neighborhoods downstream from the hidden costs of industrial shortcuts.

Why It All Still Matters

Hearing from someone who’s faced the health impacts or spent years working around powerful solvents brings home the weight of these choices. For me, digging into the details of this chemical’s history shows how industry keeps learning, and how sticking with proven safety steps rivals any new invention for making life better on the job and at home.

What Everyday Contact Really Means

Spend time around older factories, chemical plants, or industrial cleanup sites, you might hear about 1,1,2,2-Tetrachloroethane. The chemical’s name sounds intimidating and, in practice, exposure brings along a basket of problems most people overlook until symptoms show up. I’ve worked at a hazardous materials plant in my early twenties, before OSHA inspections turned rigorous. No one warned about the risks, because nearly everyone wore cloth gloves and trusted their noses—if you couldn’t smell it, it probably wasn’t there. That myth ended fast when a co-worker landed in the ER after inhaling fumes during a tank cleaning.

How Exposure Actually Hits Us

Inhalation tops the chart for risk. 1,1,2,2-Tetrachloroethane evaporates more easily than you’d expect, so breathing becomes a main entryway. Workers, people living near spill-prone sites, or anyone handling forgotten containers get exposed through air, their skin, or contaminated water. I never realized wiping a sweaty brow after handling a valve exposed my skin until the itchy chemical rash arrived a few hours later.

Body’s Reaction: Brain and Liver Take the Hit

After breathing the stuff in, people start feeling dizzy, headaches creep in, sometimes there’s nausea. Spend enough time without protection and things get serious: nerve function can falter, reaction times slow, moods swing, memory can fade. Doctors don’t label these symptoms “chemical-related” right away, but the pattern becomes clear after workplace clusters pop up. Over weeks or months, the chemical targets the liver. Blood tests show rising enzyme levels, sometimes jaundice. Folks who live in areas with older storage tanks, where spills leak into groundwater, see a higher chance of liver and kidney issues.

The Cancer Question

The Environmental Protection Agency classifies 1,1,2,2-Tetrachloroethane as likely to cause cancer. Studies in animals connect prolonged exposure to higher rates of tumors, particularly in the liver and blood. Human data stay scattered, mostly because exposed workers move or job sites close before researchers finish tracking long-term health. After my own time in the plant, yearly check-ins with a doctor became habit—not paranoia, just caution.

Why This Chemical Remains a Threat

A big part of the risk lingers in areas with aging storage or poor disposal practices. Once it leaks, cleanup gets tough and costly, so old spills often stay in the soil and water. Public awareness barely exists. Most families in affected zones never hear the names of the chemicals in their water reports, unless an activist group steps in. In places where basic protective gear feels optional, workers trade short-term discomfort for long-term consequences nobody sees right away.

Common-Sense Steps Forward

Better labeling and hazard training in older worksites cut surprises. People respond to stories—when someone in the next town over gets sick, attention picks up. Community testing of wells and air, especially near retired plants, helps families avoid casual contact with stripped-down water or soil. Stronger checks on chemical storage, along with well-publicized cleanup plans, keep forgotten stockpiles from leaking into neighborhoods. On the medical side, doctors need sharper tools to recognize problems before symptoms turn life-altering.

Knowledge, transparency, and early action protect people far better than regulations gathering dust in a binder.A Closer Look at the Risks

Spending a few years in chemical storage and handling, I’ve discovered that 1,1,2,2-tetrachloroethane isn’t a substance to take lightly. Breathing its vapors or spilling a drop on the skin brings more worry than most solutions on the shelf. The CDC and EPA point out links to liver and kidney damage, effects on the nervous system, and a potential for cancer in humans. You wouldn’t want a single slipup to threaten the crew or the community nearby.

Solid Storage Practices

A lot changes when strong solvents like this one enter the workspace. A steel drum with a tight-fitting cap offers decent security, but you need more than just a container. Keeping an eye on temperature gives peace of mind since this solvent evaporates quickly as things heat up. No chemical closet should double as a storeroom or break area—nobody wants to pair up lunch with a whiff of chlorinated vapor.

Ventilation tops the checklist. Mechanical exhaust fans make a real difference, pulling stray vapors away instead of letting them float toward unsuspecting noses. Proper labeling—bold and unmistakable—on every drum and bottle keeps anyone from filling an unlabeled jug or making a dangerous mix-up on a rushed morning.

Personal Safety Habits

Simple routines offer lasting protection. I reached for goggles, a long-sleeved lab coat, and chemical-resistant gloves any time this solvent left the shelf. Splashing seems unlikely until it happens, so skip the shortcuts. Even a splash on boots finds skin faster than you'd expect.

Those closest to the work get the highest exposure, so a reliable respirator with the proper cartridge cuts down the risk. The old “crack a window” trick doesn’t work here. The vapor is heavier than air and hugs the ground, quietly pooling around ankles and behind equipment—out of sight, not out of harm’s way.

Handling Spills and Waste

Here comes the messy part. A spill kit within reach beats any hopes of improvising. My team spent time drilling on containment, using absorbent pads, and sealing up waste. Speed matters, but so does precision. Dragging a mop or sweeping leaves behind residue and spreads risk.

Don’t take waste disposal lightly either. Pouring solvents down the drain may cost less up front, but local water agencies and regulators hand out fines without blinking. Licensed chemical haulers know their stuff. Taking a shortcut here guarantees a headache with state inspectors, and possibly a court date.

Long-Term Solutions

Solutions start well before the first drum arrives. Training sticks with a crew longer than a locked storage room, especially if the training covers real stories—burned skin, surprise leaks, and alarm bells ringing in the night. Auditing storage spaces twice a year helped me spot small problems before they racked up large repair bills or worker’s comp claims.

Hitting the books about substitution makes sense, too. Green chemistry isn’t just a buzzword. Switching to a less toxic solvent where possible shrinks storage concerns and lightens everyone’s mental load. Mistakes still happen, but the costs drop if their impact shrinks.

Care and vigilance turn every storage room into a safer place to work—a goal worth the extra time on even the busiest day.

Understanding the Chemical

Growing up near a chemical plant brought certain realities close to home. The sharp smell lingering in the air after every rainfall, the warnings taped to fences, and stories of odd illnesses in places most folks barely give a second thought. 1,1,2,2-Tetrachloroethane, for most, sounds like part of a chemistry quiz, but it plays a real-life role in a broad range of industrial processes. Used for decades as a solvent, this compound finds its way into metal cleaning, paint removers, and sometimes even as a starting point in the production of other chemicals. It carries a heavy chlorine load, making it very effective at breaking things down. This same potency is where trouble often starts.

How It Threatens Water and Wildlife

Chemicals that make their way out of barrels and into nearby streams never just disappear. 1,1,2,2-Tetrachloroethane stands as a clear example of this. It dissolves well in water, which means it can slip through contaminated soil and head straight into groundwater. Folks relying on well water might not notice anything different at first, but the buildup over time worries experts. Drinking water guidelines from agencies like the Environmental Protection Agency flag this compound as a serious concern, with links to liver and neurological problems after repeated exposure.

Wildlife faces its own set of challenges. Fish and amphibian populations pay the price when water gets contaminated. Research points to stunted growth, reproductive issues, and even die-offs when levels spike. The chemical doesn’t stick around in soil or sediment for centuries, but it persists long enough to do harm. Birds and mammals feeding near contaminated sites often collect traces in fat and tissue over time, which can work its way up the food chain.

What It Means for Human Health

It’s hard to talk about environmental hazards without mentioning the toll on people. Workers in factories using 1,1,2,2-Tetrachloroethane feel the brunt with short-term symptoms like dizziness, headaches, and nausea. Long-term effects prove worse: chronic exposure has been tied to liver cancer and nervous system damage. Rescue stories from industrial cleanups show how fast things improve when exposure drops, proving how much these compounds can shape health outcomes near contaminated sites.

Solutions and the Road Ahead

Smart regulation changes things for communities living near chemical plants. Years ago, nobody took industry waste much further than the nearest ditch. Now, tougher rules require companies to track their waste and limit how much gets dumped into waterways. Cleaner technology and better monitoring systems cut contamination risks.

What made a difference in places I’ve lived wasn’t just laws—it was neighbors getting involved. Community groups testing wells, reporting strange smells, and demanding action keep the pressure on. Removing contaminated soil or installing new filtration systems for water carry higher up-front costs, but they protect health for the next generation.

Switching to safer alternatives in manufacturing can also shrink the footprint of chemicals like 1,1,2,2-Tetrachloroethane. Some companies have already found less toxic substances that do the job without leaving behind such lasting harm. The more these choices become the norm, the less likely future generations will face the kind of risks posed by chlorine-heavy solvents.

A Chemical with Serious Consequences

Walking into a lab and seeing bottles marked “1,1,2,2-Tetrachloroethane” always put me on edge. It's not reputation alone — this chemical has had a track record for hurting those who let their guard down. A single mistake with it can have nasty consequences. So you start by treating it with respect.

How 1,1,2,2-Tetrachloroethane Puts You at Risk

This isn’t an ordinary solvent. Exposure can knock out your liver and kidney, wreck your nervous system, or burn your skin and lungs. It’s also considered possibly carcinogenic. It doesn’t take high levels to cause health problems. In the lab, I saw safety data sheets highlight dizziness, nausea, and headaches at low exposures. Short-term contact with the liquid makes quick work of your skin or eyes, which is a lesson you only need to learn once.

Building Barriers: Practical Steps for Safer Handling

The first rule: keep the stuff contained. Fume hoods are a must with anything volatile and toxic, and 1,1,2,2-Tetrachloroethane belongs firmly in this category. There’s no way I’d open a bottle of it outside proper ventilation — one whiff is enough. Engineering controls like fume hoods and local exhaust fans become non-negotiable, not only for comfort but for keeping exposure below the limits set by OSHA and NIOSH.

PPE isn’t a casual suggestion either. I always wore goggles, face shields, and nitrile or neoprene gloves. Standard latex can’t hold up against this solvent. Lab coats alone aren’t enough with splash risks; aprons made from chemical-resistant material offer an extra layer. Clothes and skin should never meet with this liquid.

Rules, Routines, and Automating Safety

Lab safety can’t be based on memory alone. In our lab, every hazardous chemical got its own clear storage and labeling — with secondary containment. Tetrachloroethane sits below eye level, away from incompatible chemicals, such as alkali metals, strong oxidizers, and even some plastics. Fire-safety storage cabinets don’t just help compliance — they offer real protection if something goes wrong.

I’ve seen what happens with a fumbled spill. Procedures for emergencies can’t just collect dust in a binder. Spill kits specific for chlorinated solvents sat near our door, and everyone trained to use them. Eye-wash fountains and showers nearby mean fast action if something splashes.

Cutting Down Exposure—And Risk

Monitoring air in the workspace kept surprises away. Using real-time detectors and regular maintenance checks meant we spotted leaks before they became problems. Access gets restricted only to people trained in handling this chemical’s quirks. Shortcuts—like using open beakers or skipping the hood even for a second—got treated seriously. Supervisors and workers looked out for each other; nobody worked alone when transferring or disposing of the stuff.

Solutions and Improvements

In the past, safer substitutes weren’t always an option, but today, seeking alternatives makes sense whenever possible. If a process can use a solvent with a better health profile, I push for that swap. Investing in closed systems for transfer and mixing makes the workspace safer for everyone. Training isn’t a box to check on an annual form — it needs repeating, sharing stories, and walking through drills. Communication, clear signage, and strict protocols create a culture where nobody gets careless.

1,1,2,2-Tetrachloroethane hasn’t changed. The way to work with it as safely as possible comes down to knowledge, planning, the right protection, and respect for the risks. Those habits enabled my lab to avoid serious incidents. If there’s one lesson, it’s this — approach every task with the humility to expect the unexpected and the preparation to meet it.